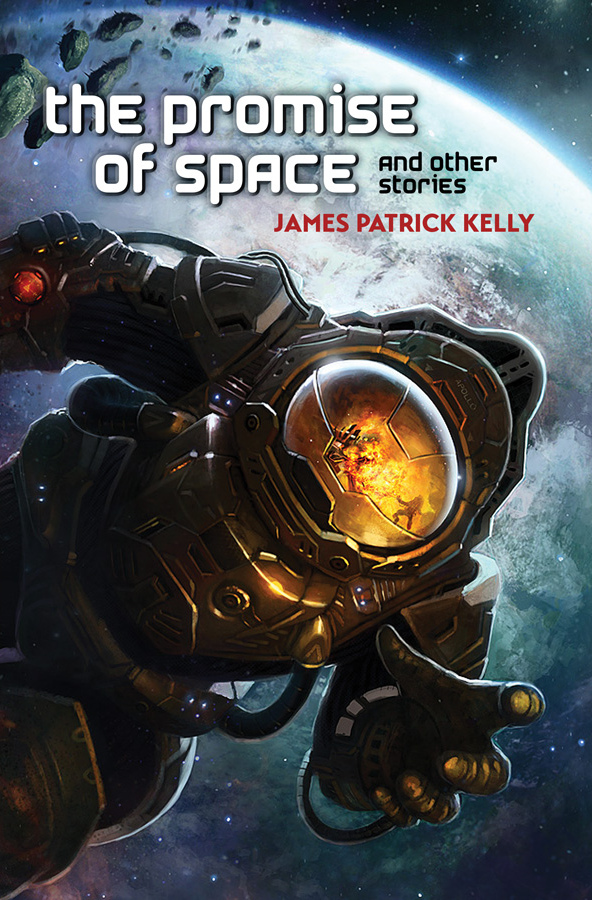

James Patrick Kelly is joining us today with his short story collection The Promise of Space and Other Stories. Here’s the publisher’s description:

James Patrick Kelly is joining us today with his short story collection The Promise of Space and Other Stories. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Hugo and Nebula Award-winner James Patrick Kelly may offer the “Promise of Space,” but he delivers so much more. The sixteen stories included in this collection demonstrate the versatility of the author as a visionary and science fiction as a genre. Exploring Directed Intelligence, space opera, and shared sensory perception, he paints vivid pictures of startling futures and fantastic landscapes. And while Kelly pushes the boundaries of technology, his focus remains always on character, giving these speculative tales of loyalty and betrayal, love and desire, the human touch . . .

What’s James’s favorite bit?

JAMES PATRICK KELLY

My favorite bit of my new short story collection, The Promise of Space, is actually a statistic. Of the sixteen stories in the table of contents, all published in the last decade, thirteen are narrated from a woman’s point of view. So? Compare that to my first collection, Think Like A Dinosaur, which came out in 1990. Just six of the fourteen stories in that book are in the point of view of a woman. Am I proud of this statistic? Well, sort of, although I’m not looking for a medal or claiming any kind of literary breakthrough. I’m well aware that when a woman publishes a persuasive male point of view, nobody is standing by with a microphone and videocam to document it. Women have been writing men since science fiction was invented. Hello, Mary Shelley!

Of course, back in sf’s so-called Golden Age, when sf was run as a boys’ club, some particularly ignorant chauvinists in our genre insisted that women couldn’t create convincing male characters. Period. End of discussion. But those were the Bad Old Days. When I first started publishing, I believed that we’d moved on from the debate about whether men can write women or whether women can write men. Now my mind has changed. I don’t think we’re there yet and maybe we shouldn’t be. I’ve observed recently that the heat of the debate has cooled and has shifted into an interesting and more nuanced conversation. One that I believe is worth pursuing.

Whether or not my thirteen women are convincing is for you to judge. All I can say is that I try my hardest to get them right. I confess that it is the externals that often flummox me. Like clothes. Shoes. Hairstyles. I remember once taking the better part of a day to figure out how to describe a manicure, having never experienced what seemed to me, as I wrote, to be a particularly gratifying experience.

For the more essential and serious aspects of characterization, I can only draw upon my own experience. I was a stay-at-home dad before that become commonplace and was usually the only dad in the company of moms. The years of my daughter’s childhood helped me redefine who I was and how I related to the world. In 1989, when Maura was nine, I wrote this in an introduction to a chapbook, “Feminism may well be remembered as the most important contribution of the Twentieth Century. Yes, more important than all the high tech: cybernetics, space exploration, nuclear physics, or biotechnology. In the next few decades, it has the potential to transform the fundamental structure of human culture.” And so it has, even as the transformations continue. With the arrogance of youth, I thought myself a feminist back then, but now I realize that I can only aspire to be a feminist. These days, I feel the weight of my examined and as yet unexamined prejudices about sex and gender, baggage from growing up male in the Fifties and early Sixties. So I worry about what you think of my thirteen women. I worry a lot.

Which brings me back to my collection and the conversation about men writing women. I needed to write an original story for The Promise of Space and for reasons that remain mysterious to me, I decided to write about a highly intelligent fembot programmed to serve the sexual needs of a rich man. Not a particularly original idea, but the twist was that her master wasn’t interested in her and she was thus sexually frustrated. In the opening sections of “Yukui!” we see how enthusiastic she is about her skeevy role as a dependent intelligence and sexual plaything. I’d hoped that the intent of the author was made plain when her antagonist, a woman, tells her:

“’Intelligent servitude is a terrible institution,’ the lifeguide said. ‘You don’t realize it, but your sidekick programming is a kind of insanity.’”

The story’s ending, in my opinion, is upbeat and feminist. You can judge for yourself, since it was just reprinted in Clarkesworld. But when I workshopped it before sending it off to my editor, Sean Wallace, at Prime, the women in my group had some hard words for me. I realized that I had not made my intent plain enough. Okay, that’s what rewrite is for. But one workshop comment has been spinning in my mind ever since. A very smart woman said, “This story wouldn’t be so hard to take if a woman had written it.”

Flash forward a few months. I did a reading at the monthly Fantastic Fiction series at the renowned KGB literary bar in New York, hosted by Ellen Datlow and Matt Kressel. The final version of “Yukui!” is just 3500 words long, the perfect length for KGB. So I read it. The book wasn’t out then and this was the first time anyone had ever read or heard the rewrite. I was a little nervous, but apparently the revised ending worked and the audience seemed happy enough. But as I read those opening sections, I picked out a couple of women, strangers to me, who were listening intently with what I took to be troubled looks on their faces. After the reading, there was some time for mingling. I worked the room toward the two women, finally plopping down at their table. “Did I pull it off?” I asked. They knew exactly what I was talking about and one of those very interesting conversations ensued. They allowed as how I won them over at the end but that they were very uncomfortable for most of the story. And then one of them said, “It would have been different if you were a woman.”

And, you know, I think she was right. I absolutely get it.

Should it have made a difference? I don’t know, but that’s a conversation I’d really like to start. However, if you don’t mind, I think it best if I just listen to what other people have to say.

LINKS:

The Promise of Space and Other Stories Universal Book Link

BIO:

James Patrick Kelly has won the Hugo, Nebula and Locus awards; his fiction has been translated into twenty-one languages. His most recent story collections were this year’s The Promise of Space from Prime Books and Masters of Science Fiction: James Patrick Kelly published by Centipede Press in 2016. His most recent novel, Mother Go, was published in 2017 as an Audible original audiobook on Audible.com. He writes a column on the internet for Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine and is on the faculty of the Stonecoast Creative Writing MFA Program at the University of Southern Maine.