Alison Wilgus is joining us today to talk about Chronin Vol 2: The Sword At Your Back. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Alison Wilgus is joining us today to talk about Chronin Vol 2: The Sword At Your Back. Here’s the publisher’s description:

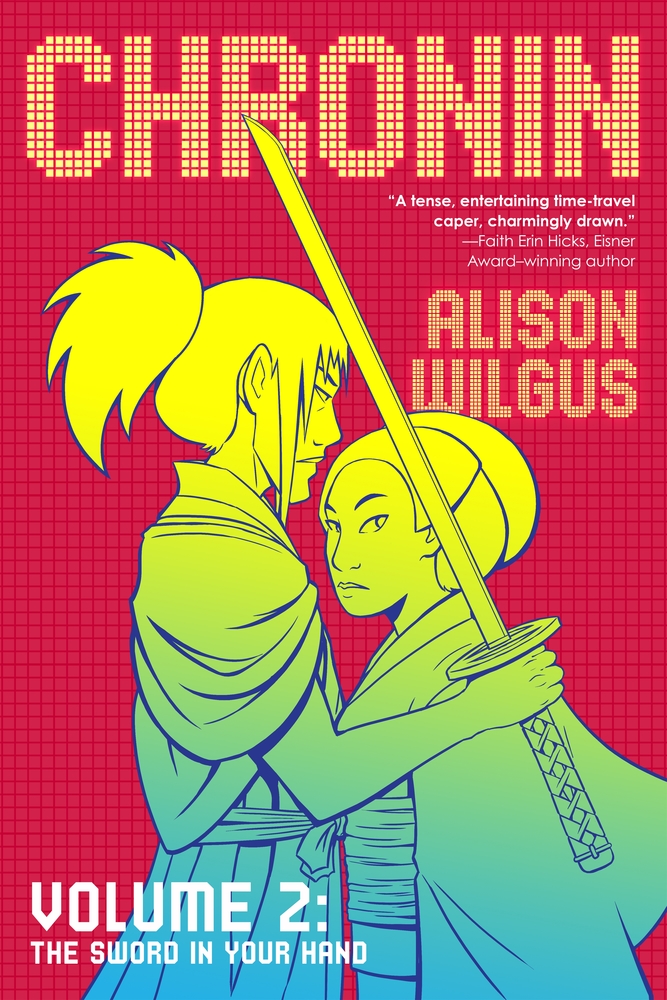

Samurai Jack meets Back to the Future in Alison Wilgus’s Chronin Volume 2: The Sword in Your Hand, a thrilling conclusion to a time-bending graphic novel duology

Japan’s history will never be the same. The timeline has veered off course with the abrupt deaths of prominent players in the nation’s past, influencers who were supposed to start the Meiji Restoration. Now Mirai Yoshida, former Japanese-American undergrad turned samurai on the lam, may never find her way back to where she belongs.

Unless a high-stakes plan is enacted. With help from her newfound friends, Mirai must instigate a peasant uprising to correct the course of history. But in order to succeed, she faces a dangerous and powerful fellow time traveler, an enemy who accidentally glimpsed his country’s destiny and didn’t like what he saw.

Chronin, Volume 2: The Sword in Your Hand concludes the adrenaline-fueled adventure that asks: when time is of the essence, is it more important to save yourself or the future?

What’s Alison’s favorite bit?

ALISON WILGUS

My favorite bit of Chronin — of the whole duology, really, but in particular this second half — isn’t something that’s in the book. The detail I hold dearest to my heart isn’t a character, or a scene, or a clever piece of worldbuilding. It’s an absence. An exorcism, maybe, of narrative ghosts that’ve haunted me for a long while.

Like many a queerball 90s teen, the path of my life was forever altered by Mulan, Disney’s 1998 animated musical about a woman who disguises herself as a man and takes her father’s place when he’s called to war.

I profoundly related to Mulan’s discomfort in the opening scenes, watching her flounder in the hyper-feminine packaging of a prospective bride. I, too, had been told that my future happiness was tied to a specific performance of womanhood; that in order to be content I would have to be desired by a man, and that men would want me to be soft and small and delicate. Men wouldn’t be interested in a tall, loud, heavyset weirdo who drew gargoyles fanart instead of doing her homework.

I adored Li Shang, Mulan’s handsome commander. I loved that he gravitated toward “Ping” even before learning his secret — before he knew that Ping was a costume, a second suit of armor which Mulan had constructed to survive amongst soldiers. And I also adored Ping in his own right, as he struggled through awkwardness and inexperience to become a heroic leader of armies, admired by his peers and respected by his superiors. I deeply envied Mulan’s successful transition into this alternate self.

Other things, however, didn’t sit so well with me.

I hated when Mulan’s new soldier friends dragged her through a sexist musical number about what made a girl “worth fighting for.” I hated that the discovery of her secret was immediately followed by hateful rejection — that she was literally cast out into the snow for daring to smuggle her womanhood into men’s business. The framework to understand transphobia wasn’t available to me as a teen, but I hated the talk of “ugly concubines” and everything surrounding it.

Mulan was my favorite film, but every rewatch took its toll. I dreaded another journey through melodramatic misogyny, enacted on-screen by a mostly male cast as part of their arcs of reform.

I’ve long been attracted to “crossdressing” stories, or to media which plays with gender. But this trope is a hell of a thing to love; it’s so often wrapped up tightly with one sort of awfulness or another. Themes of misogyny, homophobia and transphobia pop up again and again, either because the work in question is addressing those things intentionally, or because thoughtless execution results in brutal splash damage.

It’s not really surprising, looking back, that when I sat down to plan out my first ambitious solo endeavor, the main character at the heart of it was a woman who chooses to dress as a man.

Like Mulan, Mirai crossdresses in part for reasons of safety and utility — she’s concerned about her ability to “pass” as a nineteenth century Japanese woman, and worries that she’ll draw a bad kind of attention from period-natives if she tries. But also, she’s just more comfortable! She dresses in a unisex style in her own context, and when presented with two more divided options for navigating the past, she opts for the masculine one because it feels like a better fit.

Perhaps more importantly, while Mirai’s crossdressing story does involve eventual discovery, the tensions this causes have little to do with gender. Her traveling companion, for example, doesn’t care whether or not Mirai is a man — she cares that Mirai is a commoner posing as samurai, a criminal deception which puts both of them in danger.

Chronin is largely an adventure story, and so involves a dramatic confrontation — Mirai has to face down the antagonist at the root of her problems, and defend her own choices in the face of his ire. But there’s no dramatic reveal of her gender in this scene; it’s only mentioned incidentally. Mirai and her opponent are at odds because they disagree about the future of Japan, not because of who she “really” is.

Throughout both volumes, Mirai’s experience of gender is important to her personally. But it has little bearing on the plot, and is of no real concern to anyone else.

My cohort of queer cartoonists spend a lot of time talking about how we’re making the books we wish we could have read when we were younger, and while Chronin is for adults and older teens rather than kids, my own past self is very much on my mind. I built this book around Mirai, and she comfortably inhabits a trope that’s often done me wrong.

My favorite bit of Chronin is that Mirai reaches the end of it without being thrown in the snow; without being scolded and shamed for daring to conceal her “true” self. It feels good to be putting this story out into the world. I hope it finds the people who need it.

LINKS:

Chronin Vol 2: The Sword At Your Back Universal Book Link

BIO:

Alison Wilgus is a Brooklyn-based bestselling writer, editor and cartoonist who’s been working in comics for over a decade. Most of her professional work has been writing for comics, including two works of graphic non-fiction with First Second Books about aviation history and human spaceflight. Her short prose fiction has been published by Interzone, Analog and Strange Horizons. Her latest work is Chronin, a science-fiction duology from Tor books and her solo graphic novel debut. In her spare time, she co-hosts a podcast about comics publishing called “Graphic Novel TK” with Gina Gagliano.