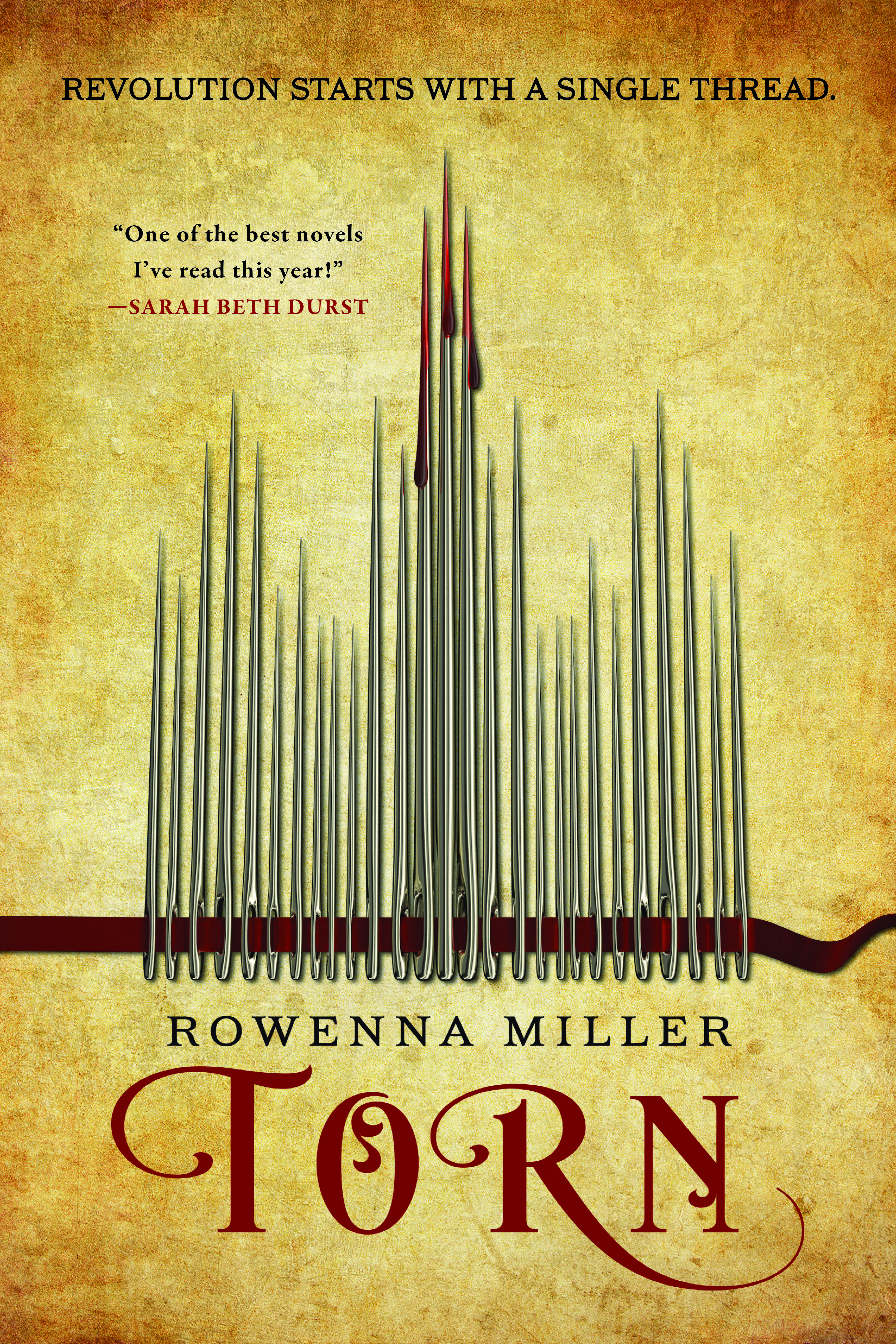

Rowenna Miller is joining us today to talk about her novel Torn. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Rowenna Miller is joining us today to talk about her novel Torn. Here’s the publisher’s description:

TORN is the first book in an enchanting debut fantasy series featuring a seamstress who stitches magic into clothing, and the mounting political uprising that forces her to choose between her family and her ambitions, for fans of The Queen of the Tearling.

In a time of revolution, everyone must take a side.

Sophie, a dressmaker and charm caster, has lifted her family out of poverty with a hard-won reputation for beautiful ball gowns and discreetly embroidered spells. A commission from the royal family could secure her future — and thrust her into a dangerous new world.

Revolution is brewing. As Sophie’s brother, Kristos, rises to prominence in the growing anti-monarchist movement, it is only a matter of time before their fortunes collide.

When the unrest erupts into violence, she and Kristos are drawn into a deadly magical plot. Sophie is torn — between her family and her future.

What’s Rowenna’s favorite bit?

ROWENNA MILLER

When we study history, we have both the benefit and the giant blind spot of knowing how it turned out. The choices historical people made end up cast in the light of the outcomes of conflict or change, and we often ascribe motivations to individuals and entire groups that only emerge as clear and discreet after the dust has settled. When it comes to revolution, we often face an even bigger blind spot—those who opposed change must have sided ethically and ideologically with “the establishment,” right?

When I began writing Torn, I knew one thing pretty confidently about my protagonist, Sophie. Though she was sympathetic to the problems the revolutionaries in her community were responding to, she was also deeply (and understandably) averse to change, having sacrificed and fought to achieve her goals of owning a business. Revolution means change. So I found myself exploring an unfolding revolution through the lens of a protagonist whose motivations are far more nuanced than “pro” or “anti” revolt—she is motivated by her professional success, by her family, and by her community more than she is motivated by ideals. She isn’t willing to risk what she loves on a dodgy gamble.

And the revolution itself—more than a dodgy gamble, it’s a morally questionable endeavor to begin with. Some members, like Sophie’s brother Kristos, are ideologically motivated. Others are motivated by anger and seem out for a kind of reversal of status that could end with something like the French Revolution’s Terror. And the nobility they’re railing against isn’t entirely corrupt—the system, which, though grossly unjust, keeps the peace, and most of the individuals, though grossly privileged, care about their country and its people. As it becomes increasingly obvious to all involved that violence is very likely necessary in establishing a fairer system based on new ideology, the question of how much death (and whose) is a fair price for change nags Sophie…and doesn’t seem to bother some of the people it perhaps should.

This ambiguity was one of my favorite parts of the book, which led to writing characters who had to face these competing motivations and their own investment in their choices. Writing Sophie and Kristos and their not infrequent spats drew their fears and hopes and problematic plans into full relief. Neither had the monopoly on logical and empathetic arguments. Kristos was right that the nation needed change, but Sophie was also right that change meant serious risk for ordinary people like them. Other characters added more nuance—Theodor and Viola, nobles Sophie encounters in her expanding business, are not entirely unaware of their unjust privilege but truly believe they are using their wealth and power to benefit the country. Depending on one’s definition of benefit, perhaps they are—offering stability at the price of the common folks’ stagnation, but can a political system that doesn’t listen to or allow for participation by the majority of its citizens ever truly benefit them?

The complications on the simple goal of “doing what’s right” made writing these characters’ responses to revolutionary ideas, and eventually actions, one of my favorite parts of writing Torn.

Yet, running contrary to this ambiguity is the presence of the charm and curse magic Sophie utilizes. Present and visible only to practitioners like her, it’s quite literally light and dark, imbuing items she charms or curses with good or bad elements. This little twist challenges the idea of complete moral ambiguity—this is a world where good and bad literally exist in a physical sense, yet the people inhabiting the world, even those handling magic itself, are not any more capable than most of us in discerning it.

And that—the juxtaposition of real good and bad with people who make a wretched tangle of right and wrong—is my favorite bit!

LINKS:

BIO:

Rowenna Miller grew up in a log cabin in Indiana and still lives in the Midwest with her husband and daughters, where she teaches English composition, trespasses while hiking, and spends too much time researching and recreating historical textiles. TORN is her first novel.