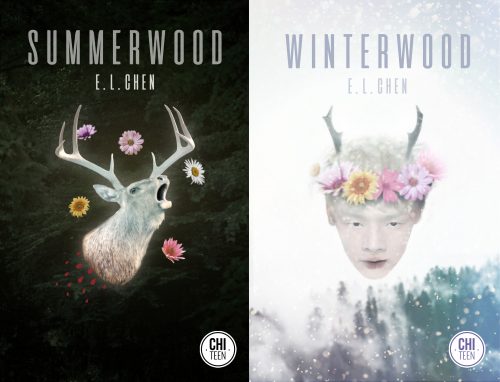

E. L. Chen is joining us today to talk about her novel Summerwood/Winterwood. Here’s the publisher’s description:

E. L. Chen is joining us today to talk about her novel Summerwood/Winterwood. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Pray you never find your Summerwood, Grandfather had said. I’d found something worse. I’d found his.

In Summerwood, twelve-year old Rosalind Hero Cheung can’t wait to spend the summer in Toronto with her teenaged sister Julie and their famous author grandfather. Years ago Walter Denison wrote a series of bestselling children’s novels about a magical land called the Summerwood. But to Hero’s dismay, Walter is cold toward his granddaughters and Julie derides Hero’s hope that the Summerwood is real.

Nevertheless, one day she and Julie stumble into the Summerwood. Ruled by the beautiful and enigmatic Lady of Summer, it is the idyllic fantasy land out of Walter’s books, complete with quaintly dressed talking animals. However, Hero discovers the Summerwood is far more sinister than Walter had ever let on. Julie is abducted and, to save her life, Hero must find the Summerwood’s sacred winter stag. Hero quickly learns that setting out on a fantasy quest is far more prosaic—and terrifying—than she’d ever imagined, and there is a steep and bloody price to pay for being the hero.

In Winterwood, three years have passed since Lindy Cheung went into the Summerwood and emerged changed and broken. Now she’s getting into trouble—starting fights, skipping school, dating unsuitable boys. After her mother grounds her—again—she runs off to Toronto to her sister, the only person who knows what really happened three years ago. But Juliet has moved on from the trauma, and Lindy finds herself back in the Summerwood, where an old enemy tells her: The stag must die again.

What’s E.L.’s favorite bit?

E.L. CHEN

Anyone who knows me personally will be able to pick out my favorite bit from Summerwood/Winterwood right away: the rabbits. The first characters that Hero, the protagonist, meets when she stumbles into the magical Summerwood are a family of anthropomorphic rabbits, and Thaddeus Cottontail quickly becomes her best friend.

Some people are dog people, others are cat people. I’m a rabbit person. Do you remember that Twitter meme in which people listed everything they could talk about for 30 minutes without prep? I only had one thing on my list: rabbits.

It all started when I volunteered at the Toronto Humane Society in my twenties. They didn’t need any more cat groomers, but would I like to start as a Bunny Cuddler? I said yes, and soon adopted two rabbits of my own. Lenny was a surly Dutch mix, and Otis was a beautiful fawn rex who was full of beans. Easy to litter-train, they had free rein of my apartment although Lenny’s distrust of hardwood floors kept him confined to a rug. They both lived over 10 years. I didn’t adopt any more after they passed away because I’d just had my son. (He was born in the Year of the Rabbit, so he’s my bunny now.)

Rabbits are not the docile children’s “starter pets” you see in pet shop cages beside the hamsters and gerbils. Those are often babies, and like us when they hit puberty they develop major attitude–or rabbitude, as we bunnyhuggers say. (Sadly a lot of pet bunnies are abandoned at this point.) They’re social creatures that observe hierarchies, like dogs, and if they think they’re the alpha rabbit they will boss you around, head-butting your shins for food and nose rubs.

If you’re lucky enough to be favored by one of these lordly lagomorphs, they’ll rub you with their chin, marking you as theirs with the scent gland beneath it. Piss them off and they’ll run away from you, flicking up a back foot. “It’s the pet that can give you the finger,” an ex-boyfriend once observed when he’d inexplicably offended Otis.

Friends think I love Easter because of all the bunny knickknacks that show up in stores. I don’t. Those rabbits are often wearing homespun outfits–like Thaddeus Cottontail in his overalls–and holding carrots. A rabbit would claw your eyes out before you could get a costume on it–as a prey animal, anything clinging to the body will slow it down–and contrary to popular belief, carrots are actually bad for rabbits.

I could go on and on.

So it was natural that in Summerwood/Winterwood I build in real domestic rabbit behavior into Thaddeus Cottontail and his family. Fellow bunnyhuggers will recognize the binkies, the angry ears, and yes, the eating of poop and the mounting. Behavior incongruous with a child’s fantasy of adorable animals that walk and talk and dress like people. To me, rabbits in clothes implies a terrible dystopia, not a twee pastoral paradise. The rabbits’ repressed natural behavior is the first clue that the Summerwood is not what it seems.

Of course this meant I got to invent some creative rabbit cursing too. “Cecals and celery!” is the most common expression the Cottontails use, cecals being the kind of poop they eat, and celery because it was the vegetable Otis would grudgingly accept if there wasn’t anything better available. And my favourite: “What in the name of Great-Aunt Clementine’s dewlap…?”

If you’d like to learn more about Summerwood/Winterwood, visit the ChiZine site. If you’d like to learn more about how awesome rabbits are, visit the House Rabbit Society website. Always adopt from a shelter, and in the name of Great-Aunt Clementine’s dewlap, please don’t give your young child a pet rabbit for Easter.

LINKS:

Summerwood/Winterwood Universal Book Link

BIO:

E. L. Chen’s short fiction has been published in anthologies such as The Dragon and the Stars and Tesseracts Fifteen, and in magazines such as Strange Horizons and On Spec. Her first novel, The Good Brother, was published by ChiZine in 2015 and her next, Summerwood/Winterwood, is out now. She lives in Toronto, Canada with her son.