Rachel Swirsky is joining us today with her short story “Love Is Never Still” in Uncanny Magazine Issue Nine.

Rachel Swirsky is joining us today with her short story “Love Is Never Still” in Uncanny Magazine Issue Nine.

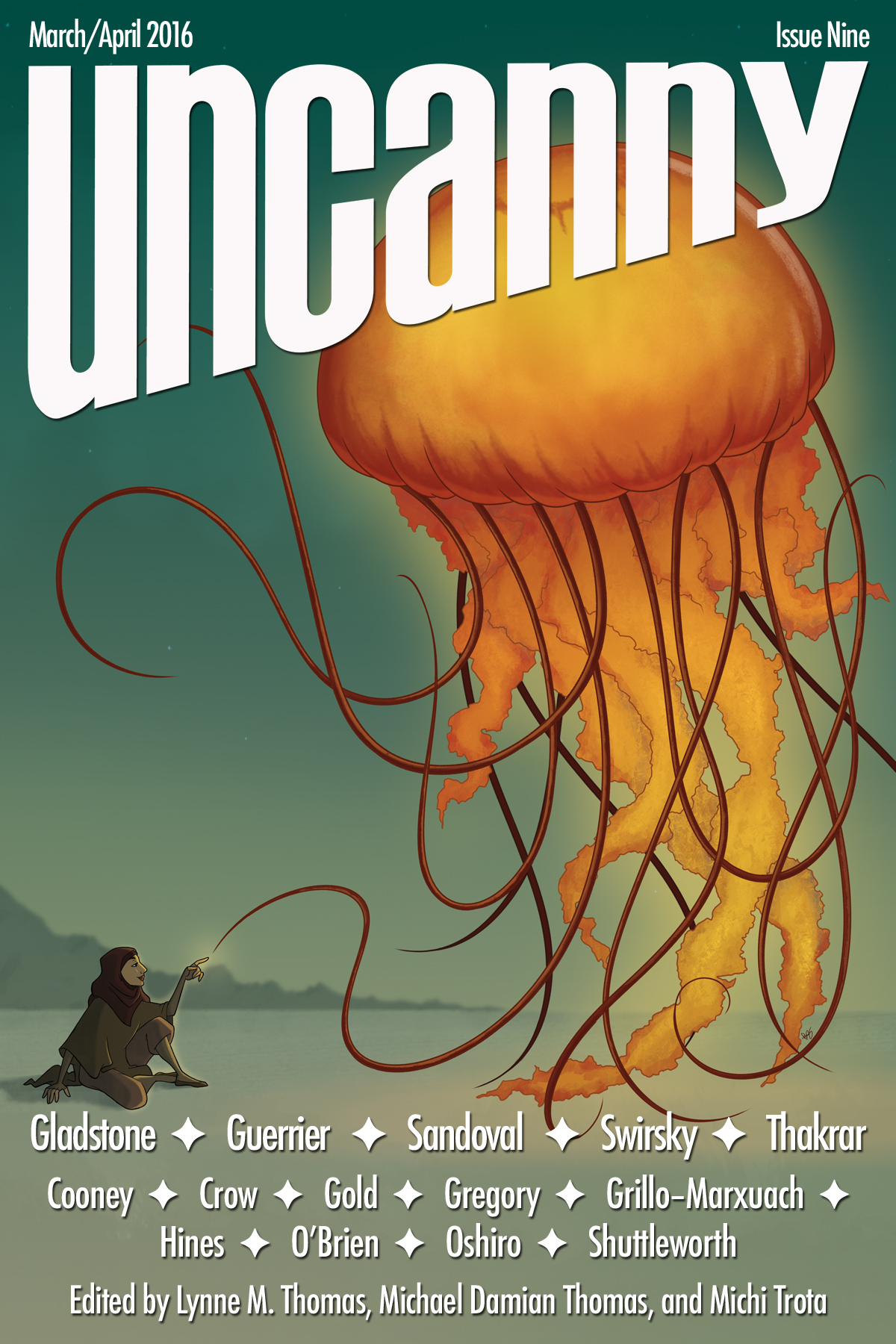

Featuring all–new short fiction by Rachel Swirsky, Shveta Thakrar, Max Gladstone, Kelly Sandoval, and Simon Guerrier, classic fiction by Daryl Gregory, nonfiction by Jim C. Hines, Kyell Gold, Javier Grillo–Marxuach, and Mark Oshiro, poems by C. S. E. Cooney, Jennifer Crow, and Brandon O’Brien, interviews with Rachel Swirsky and Simon Guerrier, and Katy Shuttleworth’s “Strange Companions” on the cover.

What’s Rachel’s favorite bit?

RACHEL SWIRSKY

When I was very young, my parents bought me D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths. I dearly loved it. In fact, I tried to proselytize it on the preschool playground. Well, by proselytize, I mean “I made them play make believe about Greek myths,” but I had a brief period of believing they were true. What? Greek gods were neat. The end of the book indicated that all the Greek gods had died, but having been raised in a culture where gods are known to die and later live again, that didn’t seem like a huge barrier.

In high school, I got the usual Edith Hamilton, and a good dose of Greek plays, from Antigone to Lysistrata. In college, I studied playwriting and acting, and discovered a new range of theatrical adaptations. There were new interpretations, like the production of Iphigenia at Aulis rewritten from Clytemnestra’s perspective, and like Zimmerman’s take on Ovid, Metamorphoses, which is partially staged in a pool.

Something I really like about the way many theaters perform Greek myths is that time and anachronisms are often allowed to slip freely. The props and dialogue are frequently at a disjunct. After thousands of years, Greek myths are meta-fiction of themselves. Every version owes its existence to stories told and told and told again. New generations bring their tools for understanding. Plays can feature both old-fashioned choruses and cell phones, or be significantly more daring than that.

While I was in graduate school, one of my fellow students wrote a novel based on Antigone that aimed to do the same things as those plays. Time, props, dialogue—all slipped between time frames according to an underlying logic the author knew, but the reader had to learn. It’s trickier in prose because theater relies on visuals to emphasize what they’re doing, but the results in my classmates’ novel were extremely striking.

All of these experiences helped me learn that working with Greek myths gives you an enormous toolbox in terms of style and content. So when I began writing my version of the Galatea myth, “Love Is Never Still,” my mind was already full of possibilities for alternate structures and ways to play with the story.

“Love Is Never Still” retells two myths simultaneously. One: the sculptor who fell in love with his statue, Galatea, and wished her to life. Two: Aphrodite’s love triangle with Hades and Hephaestus.

My favorite bit about “Love Is Never Still” is probably also my least favorite bit: the complex layers I built in over the course of four months of intense revision.

First, there are the points of view. The story begins with the sculptor, and moves on to Galatea—fair enough. Later, we hear from Aphrodite, Hephaestus, Ares, Zeus, the Fates, death, weather phenomena and some inanimate objects, for a total of about fifteen different perspectives. I actually tried writing some of the sections in the format of a traditional Greek chorus, in iambic pentameter and everything, but thank goodness I dropped that before it got too far.

It’s a little unusual to give a point of view section to a pedestal, but as I said in my interview for Uncanny Magazine, it felt intuitively right—if I was giving speaking roles to forces like death and love, it made sense to look at the mundane end of the spectrum, too.

Pedestal

Where there were feet upon me, there are divots, and I am cold.

The text is also heavily layered, which took me a lot of time. There are a number of passages that are meant to be read two ways. It was difficult to hit the right pacing for that, so that both readings seem well-crafted and seamless.

Mortals—even sometimes gods—forget the finesse required for working gold… They forget those fingers must know the delicacy of repoussé. They must, with great precision, caress gold’s most tender places with surpassing gentleness until it molds to his will.

I tried to make the text as specific and evocative as possible with research details. I spent some afternoons chasing down things like the ingredients of ancient perfumes (“balsam and cinnamon, hyacinth and lily, styrax and sweet rush”), or the color of ancient apples (pink). The most beautiful descriptions I found were from books on ancient ivory trading where I read about “silver and electrum and carnelian and malachite. [Hephaestus] embosses jewelry with trees and horses and dancers, and adorns the hilts of his weapons with granulated gold. He ornaments gods’ palaces with panels of open work ivory, and oak–carved furniture inlaid with ebony.”

Where possible, I also layered in elements from the original myths. Several details are from Ovid. At other times, when describing the gods, I used theoi.com to find more about their estates and sacred creatures, for instance Ares’ iron palace, and Aphrodite’s cockle shells and myrrh.

Some pieces of the text are crafted to act as call and response to each other. Summer and Winter speak at opposite ends of the story, and use the same sentence structures to describe events. Aphrodite’s understanding of love is constantly in flux, but always stated with the same determination. She loves both Ares and Hephaestus, although they are opposites, and the sentences with which she declares that love are mirrored.

Of Ares, she says:

Love is a spark, a winging bird, a waterfall splash. It is immediate; it is urgent; it is spontaneous. Like Ares, it moves with perfect, bold unity. It is a fully embodied moment, experienced with every incendiary, saturated sense. It is the smell of a lover and the bite of a provocative glance. I am love, and I am all these things.

And of Hephaestus:

Love is a mountain that swallows ages. It endures a thousand winters, and a million storms, and never erodes. It is steady; it is patient; it is sheltering. Like Hephaestus, it wields its hammer boldly, but also remembers the value of gentleness. It is waking to your lover’s dreamy morning murmur, and the smell of his skin that lingers in his linen. I am love, and I am all these things.

I used to write poetry (who knows—maybe I will again someday) and its great pleasure was the attention I could pore over every word. With a story like this, which I worked on intensely at the line level for about four months, I was almost able to approximate that level of control. I’m immensely proud of how much complexity there is going on in this story—immensely proud, but also ready to make some time for writing simply.

LINKS:

BIO:

Rachel Swirsky is a short story writer living in Bakersfield, California. Her short fiction has been nominated for the Hugo Award, the Locus Award, the World Fantasy Award, and the Sturgeon Award. She’s twice won the Nebula Award: in 2010 for her novella, “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” and in 2014 for her short story, “If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love.” She graduated from the Iowa Writers Workshop in 2008 and Clarion West in 2005.

I dunno, she says she doesn’t write poetry, but this is a poem if ever I’ve seen one (as was “Dinosaur”).