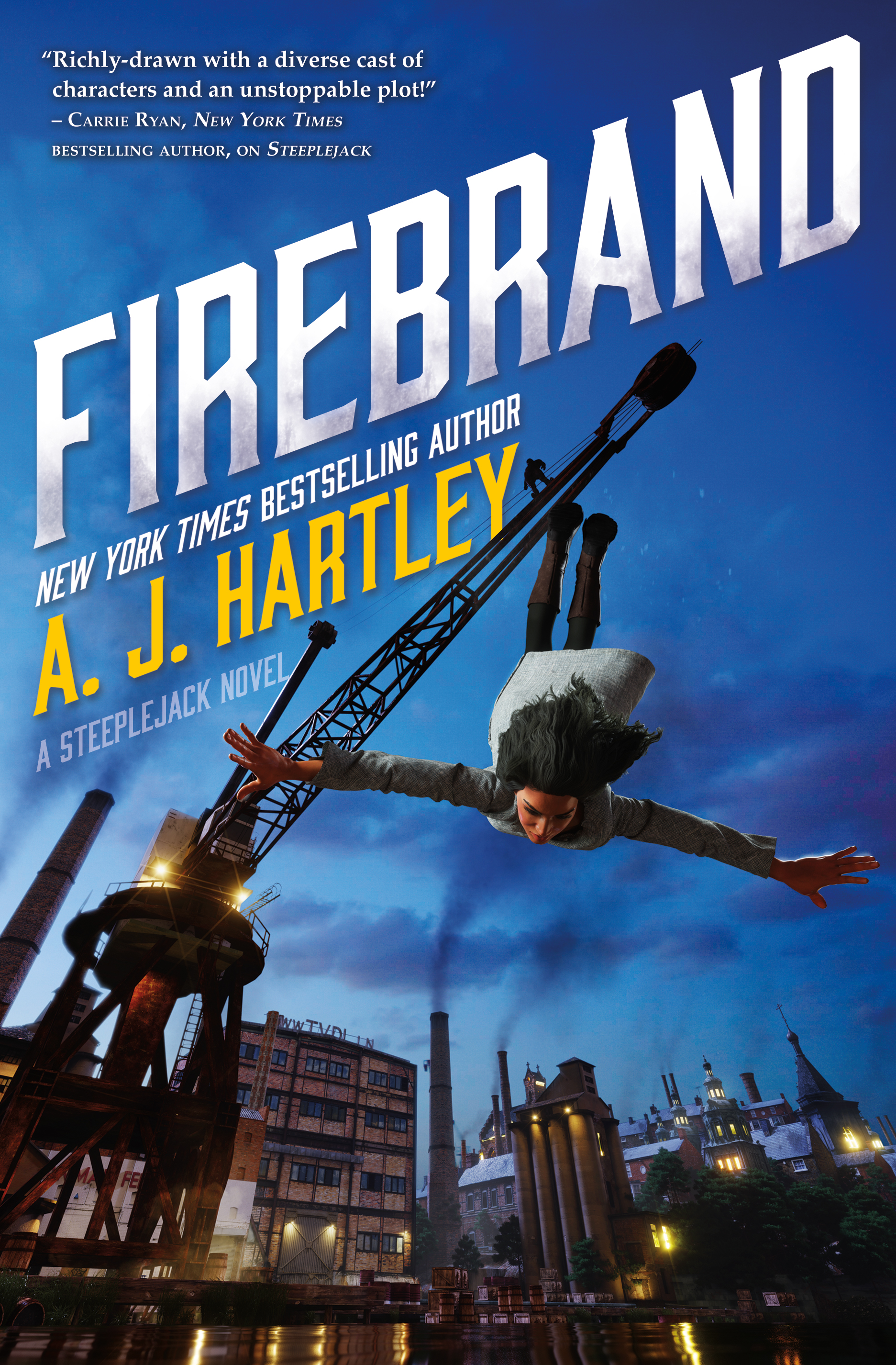

A.J. Hartley is joining us today with his novel Firebrand. Here’s the publisher’s description:

A.J. Hartley is joining us today with his novel Firebrand. Here’s the publisher’s description:

New York Times bestselling author A. J. Hartley returns to his intriguing, 19th-century South African-inspired fantasy world in Firebrand, another adrenaline-pounding adventure.

Once a steeplejack, Anglet Sutonga is used to scaling the heights of Bar-Selehm. Nowadays she assists politician Josiah Willinghouse behind the scenes of Parliament. The latest threat to the city-state: Government plans for a secret weapon are stolen and feared to be sold to the rival nation of Grappoli. The investigation leads right to the doorsteps of Elitus, one of the most exclusive social clubs in the city. In order to catch the thief, Ang must pretend to be a foreign princess and infiltrate Elitus. But Ang is far from royal material, so Willinghouse enlists help from the exacting Madam Nahreem.

Yet Ang has other things on her mind. Refugees are trickling into the city, fleeing Grappoli-fueled conflicts in the north. A demagogue in Parliament is proposing extreme measures to get rid of them, and she soon discovers that one theft could spark a conflagration of conspiracy that threatens the most vulnerable of Bar-Selehm. Unless she can stop it.

What’s A.J.’s favorite bit?

A.J. HARTLEY

In Firebrand, the second book of my vaguely African, steampunky Steeplejack series, the heroine, Anglet Sutonga, goes to visit her employer’s country estate. Ang is a city girl, and she has a dread of wild animals, having grown up with all the myths and horror stories of what lurks outside the city walls. She’s a bit freaked out by the fancy house in all its Victorian formality, and—left alone to wait for her employer in an elegant withdrawing room—she starts getting antsy.

Time passes: ten minutes, twenty.

It’s odd. She goes out into the hallway and calls for him, but there’s no answer. She starts exploring the extensive ground floor of the great house, but it is silent and deserted: no staff, no servants, no sign of her boss or his family. It’s late, and, torn between irritation and anxiety, she finds her way to the kitchens where a courtyard door has apparently been left unlatched. It’s open, flapping in the night breeze but, as she goes to close it, she realizes that something is out there in the dark.

Something big.

A shadow moves. Then another. Whatever it is, there are several of them.

Then they start that mad, distinctive chuckling, and she realizes;

Hyenas!

She turns to flee into the house but finds there are more already inside, skulking behind the kitchen cabinets…

I’ll say no more about what happens next, but I hope you can see just a little of why I love this bit. Partly it’s because I put Ang in a situation where her usual skills (her climbing ability) will not help her, forcing her to be smart and resourceful in other ways. And partly the moment plays on some of her darkest fears about the nature of the country around her. Hyenas are scary animals. Big, rogue males have been known to attack people by themselves. A pack can bring down anything that walks the bush…

But there’s more to it than that. Because while hyenas are potentially terrifying by themselves they are even more terrifying indoors. I know that sounds crazy, but think about it. Some of the added dread comes from being up close to the creatures in a confined space, but some of it is also the sheer visceral wrongness of wild things inside a nice, safe, homey space. Think of how unnerving it is to have a bird fly into your living room, say or—in story terms—think of the wolf inside Granny’s cottage in Little Red Riding Hood. To take a more recent example, remember the velociraptors in the kitchen scene in the original Jurassic Park.

What makes these animals so frightening is their juxtaposition with the tame and ordinary spaces where we live: the wild inside the domestic. So the hyenas become more scary because they are surrounded by things which are familiar and ordinary, the trappings of everyday life like tables and chairs and ornaments and paintings positioned next to slavering, hunting beasts. It’s not just that the animals are frightening; their being indoors violates our sense of our human sophistication.

And I didn’t just make it up. I’ve never been in a confined space with a hyena (thank God—though there are accounts of hyenas going into houses and attacking people) but I did have a thoroughly unnerving experience while traveling in South Africa. I left the door of my little cottage unlocked for a minute and a watchful baboon—not as scary as a hyena for sure, but a sizeable monkey with claws and sharp teeth—got into my kitchen. Baboons are clever, unafraid or humans and potentially quite dangerous. I tried to shoo it out, but it got up on the counter–-which put it’s eyes level with mine—and stared me down. I got it out eventually (after it had rifled through my cabinets for sugar packets) but I don’t mind saying that the whole experience was deeply unsettling!

I’ve always loved animals and been absolutely fascinated by them. But some beasts belong outdoors. When they get inside it’s like gravity has been switched off. The world stops behaving the way it’s supposed to and all those protective comforts which tell us that we’re not animals fall away and we’re left with our primal and most basic instincts.

No wonder Ang was terrified.

LINKS:

BIO:

A.J. Hartley was born and raised in northwest England, but left the UK after his undergraduate degree to work in Japan. Three years later he went to graduate school at Boston University, completing an MA and Ph.D. in English. After a decade working in Georgia, he became the Robinson Professor of Shakespeare Studies at UNC Charlotte, where he teaches and publishes on performance history, theory and criticism. He is also an Honorary Fellow at the University of Central Lancashire (UK).

He is the New York Times bestselling author of 15 novels in multiple genres for adults and younger readers, some of which have been translated into 28 languages. His recent work includes Steeplejack, a fantasy adventure about a girl who works in the high places of a city world resembling Victorian South Africa; Cathedrals of Glass, a YA scifi thriller about a group of teens who crash-land on a supposedly deserted planet, and Sekret Machines, a multi media project about unexplained aerial phenomena co-authored with Blink 182/Angels and Airwaves founder, Tom DeLonge. He has also written the Darwen Arkwright series for kids, the Will Hawthorne books (Act of Will etc.), award winning adaptations of Macbeth and Hamlet, and several archaeological mysteries.