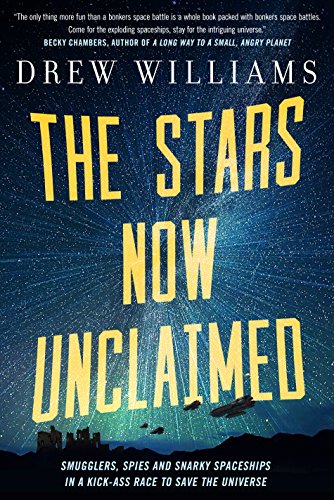

Drew Williams is joining us today with his novel The Stars Now Unclaimed. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Drew Williams is joining us today with his novel The Stars Now Unclaimed. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Jane Kamali is an agent for the Justified. Her mission: to recruit children with miraculous gifts in the hope that they might prevent the Pulse from once again sending countless worlds back to the dark ages.

Hot on her trail is the Pax–a collection of fascist zealots who believe they are the rightful rulers of the galaxy and who remain untouched by the Pulse.

Now Jane, a handful of comrades from her past, and a telekinetic girl called Esa must fight their way through a galaxy full of dangerous conflicts, remnants of ancient technology, and other hidden dangers.

And that’s just the beginning . . .

What’s Drew’s favorite bit?

DREW WILLIAMS

“Fuck you,” she murmured, the words gentle, almost astonished. “Fuck your sorry.”

That’s it; that’s my favorite line from The Stars Now Unclaimed. As far as I’m concerned, if a character is funny, that means the reader likes them more and cares more about what happens to them – so my characters have a tendency to converse in rapid-fire bursts of wordplay and sarcasm. Every once in a while, though, those defenses get stripped away, and you’re left with the true nature of the characters, and in this particular case, that true nature was ‘in pain’.

The line comes at almost the exact midpoint of the novel, where Jane Kamali, our protagonist, has just revealed her own culpability in the great catastrophe that has befallen the universe. It was kind of a ‘live or die’ moment as I was writing the novel: I had to find a way to let these disparate characters react naturally to this new, horrible information, to react in a way that fit with who they’d been before they learned this, while at the same time not alienating them from each other so much that they wouldn’t be able to come together and stop the threat the entire novel was focused around.

The initial genesis of The Stars Now Unclaimed was my lifelong obsession with the atomic bomb, an obsession more with the decision to drop it, rather than the ramifications – both purposeful and unexpected – of its use. My favorite quote in the world is the (possibly apocryphal) exchange between Robert J. Oppenheimer and Kenneth Bainbridge, immediately after the first successful test of the Manhattan Project:

Oppenheimer (quoting from the Baghavad Gita): ‘I have become Death, destroyer of worlds’.

Bainbridge: ‘Yeah, we’re all sons of bitches now’.

Both men knew the force they were about to unleash upon the world might ultimately have more destructive repercussions than the entire war it had been built to stop, but they – and General Eisenhower, and President Truman, whose quote ‘the buck stops here’ is given entirely new meaning in the context of the bomb – decided to move forward anyway, and the rest, as they say, is history.

I decided to set The Stars Now Unclaimed in a sort of post-apocalyptic space opera setting – I got to play with fancy toys like spaceships and sarcastic AI, whilst also getting down into the dirt and the ruin of post-apocalyptic desperation – but that conversation between Oppenheimer and Bainbridge was always in the back of my mind: an apocalypse starts somewhere, after all. Someone made the decision to do this to the galaxy, even if this wasn’t their intention. And the things we don’t intend sometimes have significantly more far-reaching consequences than those we do; none of us can see all ends.

One of my characters, in particular – an AI called ‘Preacher’, who speaks the above quote – was given reason to be especially bitter about the apocalypse: it had doomed her people to a kind of slow-motion genocide, no technology was left to create more of her species. So when she learns of Jane’s role in the unintended destruction of her entire species – when Jane, somewhat fumblingly, tries to justify what she did, why the decision was made, how it was carried out – the above line is her response. She doesn’t care why it happened, why her people are slowly vanishing from the universe: it truly doesn’t matter. There’s nothing at all Jane could say, to defend what the Preacher sees as the indefensible.

I didn’t expect the Preacher to say those words. I went into the scene with the mentality of ‘let’s just see how she reacts’; I’d expected rage, maybe, a kind of fury that would test the other characters. Instead, I got grief, and despair. The Preacher had been looking for an answer as to why her people were dying, and when she found it, it was no universal truth, no ‘there was a reason after all’: it was just people, trying to do something good, and fucking up despite it. Jane apologizes, and she means it, because she never intended for the apocalypse to happen – to go back to the metaphor of the atomic bomb, she meant to detonate a single weapon over Hiroshima (still a difficult moral decision in and of itself), not to set the entire planet’s atmosphere on fire.

The Preacher hears that apology, acknowledges it, and doesn’t care. Because she has her own pain to deal with, her own shock to process, and that’s too big for her to move beyond in that moment, and who can blame her? ‘Fuck you. Fuck your sorry.’ That doesn’t mean Jane was wrong to attempt to apologize, and it doesn’t mean the Preacher was wrong to reject it. Like I said about unintended consequences above: sometimes the things we try to do, and fail in, say more about who we are than where we succeed.

So anyway: that’s my favorite bit. Two people, trying to find a way around the wrong one of them has done, and in that moment, failing. It just feels more honest, somehow.

LINKS:

The Stars Now Unclaimed Universal Book Link

BIO:

DREW WILLIAMS has been a bookseller in Birmingham, Alabama since he was sixteen years old, when he got the job because he came in looking for work on a day when someone else had just quit. Outside of arguing with his coworkers about whether Moby Dick is brilliant (nope) or terrible (that one), his favorite part of the job is discovering new authors and sharing them with his customers.

I’m curious about the reference to General Eisenhower. I was not aware that he was involved in the decision to use the atomic bomb or indeed in any aspect of the war against Japan after being appointed to lead the allied effort in Europe.