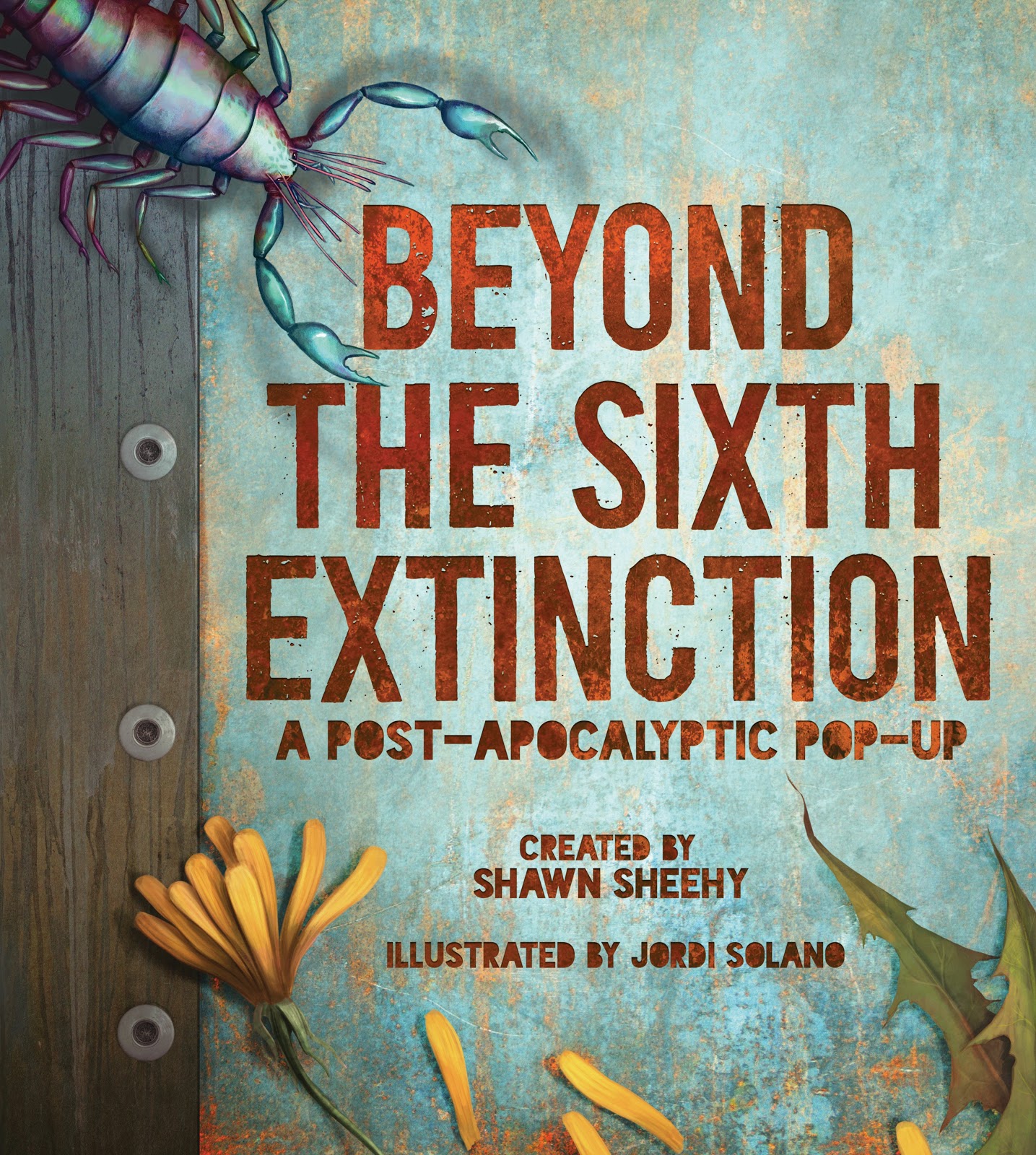

Shawn Sheehy is joining us today with his post-apocolyptic pop up book, Beyond the Sixth Extinction. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Shawn Sheehy is joining us today with his post-apocolyptic pop up book, Beyond the Sixth Extinction. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Elaborate pop-ups feature some wonderfully creepy creatures that just might dominate the ecosystem — and be essential to our planet’s survival — in an eerily realistic future world.

Whether or not we know it, the sixth global extinction is already underway, propelled not by a meteor but by human activity on Earth. Take a long step forward into the year 4847 with the help of stunning pop-ups portraying eight fantastical creatures, along with spreads and flaps presenting details about each one. Paper engineer Shawn Sheehy envisions the aftermath of extinction as a flourishing ecosystem centered around fictional creatures that could evolve from existing organisms. Promising high appeal for curious kids and science fiction fans of all ages — and plenty of food for discussion in and out of a classroom — this evolutionary extravaganza offers a timeline of the six extinction events in Earth’s history, a “field guide” to each creature, a diagram of species relationships, a habitat map of the (imagined) ruins of Chicago, and an illuminating author’s note.

What’s Shawn’s favorite bit?

SHAWN SHEEHY

There is no cute in “Beyond the Sixth Extinction.” There are no puppies, pandas or chipmunks. Creatures such as these fail to fit the profile (with the possible exception of puppies; see below) of organisms that might endure into the fifth millennium. Cute has poor prospects for survival.

These creatures also fail to fit my aesthetic profile for the near future.

Science fiction writers either imagine things they would like to see come true (transponders—flip phones), or they imagine things that they don’t want to see come true (insert any post-apocalyptic scenario here.) Place me solidly in the second camp. Imagining a creepy future helps me to engender communal affection and a sense of conservation for the diversity and wonder of the wild world— a world that, sadly, is rapidly vanishing.

So. I creep it up.

While I was in the idea generating stages of BT6X, I stumbled across a useful passage in Stephen Jay Gould’s “Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History.” He comments on how much more popular radial symmetry was as a body form in the earth’s past. He directs our attention to the fossil evidence of these creatures found in the Burgess Shale.

Contemporary examples of creatures with radial body form symmetry include sea stars and sea anemones. Humans tend to be much more familiar with bilateral symmetry, since that is what we exhibit—as well as ALL OTHER TERRESTRIAL ANIMALS. Crazy, huh? Being radial evidently only works in the water.

I leaned a bit on radial symmetry in creating the creatures in BT6X. I leaned heavily on juxtaposition—taking features of two different creatures and whipping them up in a blender. For most of my creatures, there is a primary source in the juxtaposition; essentially, the 21st-century creature from which the 49th-century version evolved. The secondary source creature lends characteristics that make the primary creature more alien.

The rotrap (an elision of “roach” and “trap”) in BT6X is a solid example of this birthing-in-a-blender approach. The primary source creature is the common house mouse. The mouse, incidentally, readily fits the profile for a creature that will survive the sixth extinction. It is omnivorous— a trait that depends on a certain intelligence. It is adaptable. It thrives in human-made environments.

I wanted contrast for the secondary source creature, so I chose the sea anemone. The anemone’s radial symmetry introduces creepiness to the rotrap because the feature is utterly alien on land. Admittedly, I was also attracted to an evolutionary function here: creatures like sea stars are thought to have once been bilaterally symmetrical, and they eventually evolved to become radially symmetrical.

If sea stars can do it, why can’t mice?

The transformation began with sitting the mouse on its hindquarters and treating it like an upright tube, with a digestive tract down the middle. I migrated the mouse’s hind limbs to a position near the fore limbs, giving it the appearance of having four arms distributed evenly around its head. Like a sea anemone, the waving arms grab nearby insects and push them into the rotrap’s mouth.

I included the anemone’s sedentary feature. Many sea anemone tend to stay rooted in one place for long periods of time. Rooting a land animal required a mechanism, a method of predator evasion or defense, and a way to reckon with a digestive system that suddenly had no outlet.

The obvious solution to creating a rooting mechanism was to use the tail. The rotrap’s tail developed branches and the root hairs that can work themselves into a substrate. In this case, the substrate is the vertical masonry of the cooling towers of defunct nuclear power plants.

This nuclear vertical brick environment solves the problem of predation. Being rooted high up on a wall allows the rotrap to evade non-winged predators. Living in a highly radioactive environment helps them escape most others. (This environment does not, however, affect the proliferation of various insects that feed the rotrap.)

As for the plugged up digestive tract? I simply made it a two-way street—whatever goes down gets digested, and then the waste comes right back up again.

Creep accomplished.

LINKS:

Beyond the Sixth Extinction Buy Link

BIO:

Shawn Sheehy is the award-winning creator of Welcome to the Neighborwood. Passionate about pop-up books, he works sculpturally with the book format and presents workshops on pop-up engineering across the country. He lives in Chicago.