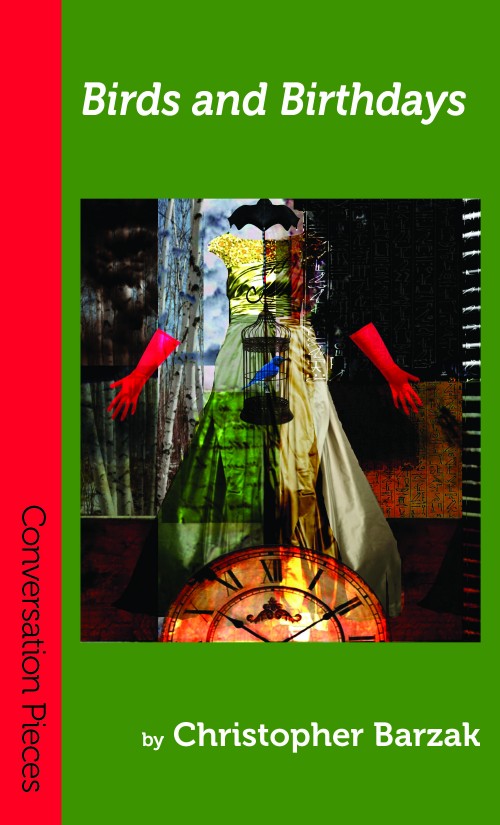

There’s a reason why Christopher Barzak’s fiction keeps getting a lot of attention during awards season. He’s a beautifully lyrical writer with a gift for evoking strong emotions. I’m a big fan, in case that isn’t clear, so I was very excited to hear that he has a new short story collection out. More accurately, it is three stories and an essay surrounding three surrealist painters and paintings. That it is based on and around paintings gives me a delicious and heady thrill.

There’s a reason why Christopher Barzak’s fiction keeps getting a lot of attention during awards season. He’s a beautifully lyrical writer with a gift for evoking strong emotions. I’m a big fan, in case that isn’t clear, so I was very excited to hear that he has a new short story collection out. More accurately, it is three stories and an essay surrounding three surrealist painters and paintings. That it is based on and around paintings gives me a delicious and heady thrill.

Why don’t we have him tell you about his Favorite Bit.

CHRISTOPHER BARZAK:

When I was a kid, I wanted more than anything to be able to draw and paint. I had a little sketchbook that I’d happily draw in

during down times in school, during church, or at home when I wasn’t reading something. I may have even, at this time, wanted to be an artist more than a writer. Unfortunately, though, I had no innate talent, just a desire, and what latent skills I might have possessed were never developed through proper instruction. Finding art classes would have been difficult in the rural area of Ohio where I grew up anyway, and even if they would have been accessible, it would have been a luxury that would have put a wrench in my parent’s budget of money and time and energy.

So instead of drawing and painting, I became a writer.

Words are the poor artist’s choice of materials to work with. They cost very little. You can find them everywhere—in magazines and dictionaries and novels and instruction pamphlets—and the only canvas and the only brush you need to apply them are tablets of lined paper and a pencil or pen. Those were easy to come by, and the library provided me with my earliest guides to making stories, which, I later realized, was the thing I was truly seeking out when I looked into the canvas of a painting or attempted to sketch a scene in my sketchbook. It was Story that I wanted to shape, to create.

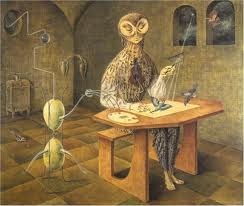

But even as writing became my medium for creation as a child and then as a teenager and then, even later, as a twenty-something, I still found myself lingering in museum hallways, wishing I knew how to bring the images in my imagination to such vivid life as is possible in a visual medium like art. I especially wished for this when I came across a group of women surrealist painters who I’d never heard of, whose paintings struck a chord deep inside me that no other surrealist art had ever touched: Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning. They painted images of women in the most fantastical of contexts:

A giantess standing on the shore of a rustic village where the villagers have raised their pitchforks and guns at the sight of her.

A Bird Woman whose sketches and paintings of birds literally fly off the page or canvas once she has infused them with starlight and music.

And a woman who stands in the starkest of apartment buildings, where the hallways seem endless, and doors open and close of their own accord, and an unidentifiable winged creature keeps her company.

How (or why might be a better question) had I never heard of them?

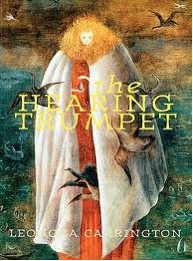

I had pop posters of surrealist art from a young age, but they were all of the likely suspects: Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Rene Magritte. They were who seemed the most in reach (and this was prior, of course, to the internet creating a space where so much information could be accessed). The women artist’s who I ran across by accident (only by having seen the cover of Leonora Carrington’s novel, The Hearing Trumpet, for which she also had contributed the cover with her painting called “The Guardian of the Egg” or “The Giantess”) led me on a search for more of their art, more of their histories, both personal and as artists in a movement where, despite its declarations to change the world’s old hierarchies, had tended to be a bit of a boy’s club.

It was then, in my mid-twenties, that my desire to paint and my writing began to merge consciously. I started a small project based on my discovery of these three women and their paintings, and began to write a triptych of stories that were inspired by their paintings. And luckily, some years later, my desire to make this tiny book out of my desire to paint, has finally come to fruition.

Writing Birds and Birthdays was kind of the opposite experience of writing a story that later comes to be illustrated. Instead, I got to take pictures and paintings and create a story from those images. For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been writing about the process at my own blog, describing the unique experience it was to create each story, and while I never have fulfilled my desire to be a painter, in the end I got something different: the fulfillment to interact, as a writer, with a group of painters whose work floored me. In the end, I got to make the kind of stories that I wished I could paint.

This was my favorite bit about writing Birds and Birthdays (and I thank Timmi Duchamp, publisher at Aqueduct Press for bringing the book out): learning about a group of women artists and their art that had, for a long time, been invisible. And also learning that, sometimes, the things we most want will never be achieved, for a variety of reasons and circumstances, but that often those frustrations can lead us into finding ways to adapt those desires into forms that are in our reach.

I hope readers of this book might, at the very least, find their way into the worlds of the artists who inspired the stories.

RELEVANT LINKS:

BIO:

Christopher Barzak grew up in rural Ohio, went to university in a decaying post-industrial city in Ohio, and has lived in a Southern California beach town, the capital of Michigan, and in the suburbs of Tokyo, Japan, where he taught English in rural elementary and middle schools. His stories have appeared in a many venues, including Nerve, The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Teeth, Asimov’s, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His first novel, One for Sorrow, won the Crawford Award for Best First Fantasy Book. His second book, The Love We Share Without Knowing, is a novel-in-stories set in a magical realist modern Japan, and was a finalist for the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the James Tiptree Jr. Award. He is also the co-editor of Interfictions 2, and has done Japanese-English translation on Kant: For Eternal Peace, a peace theory book published in Japan for Japanese teens. In August 2012, his collection, Birds and Birthdays, was published by Aqueduct Press. In March 2013, his full length collection of short fiction, Before and Afterlives, will be published by Lethe Press. Currently he lives in Youngstown, Ohio, where he teaches fiction writing in the Northeast Ohio MFA program at Youngstown State University.