Nancy Kress is joining us today with her novel Tomorrow’s Kin. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Nancy Kress is joining us today with her novel Tomorrow’s Kin. Here’s the publisher’s description:

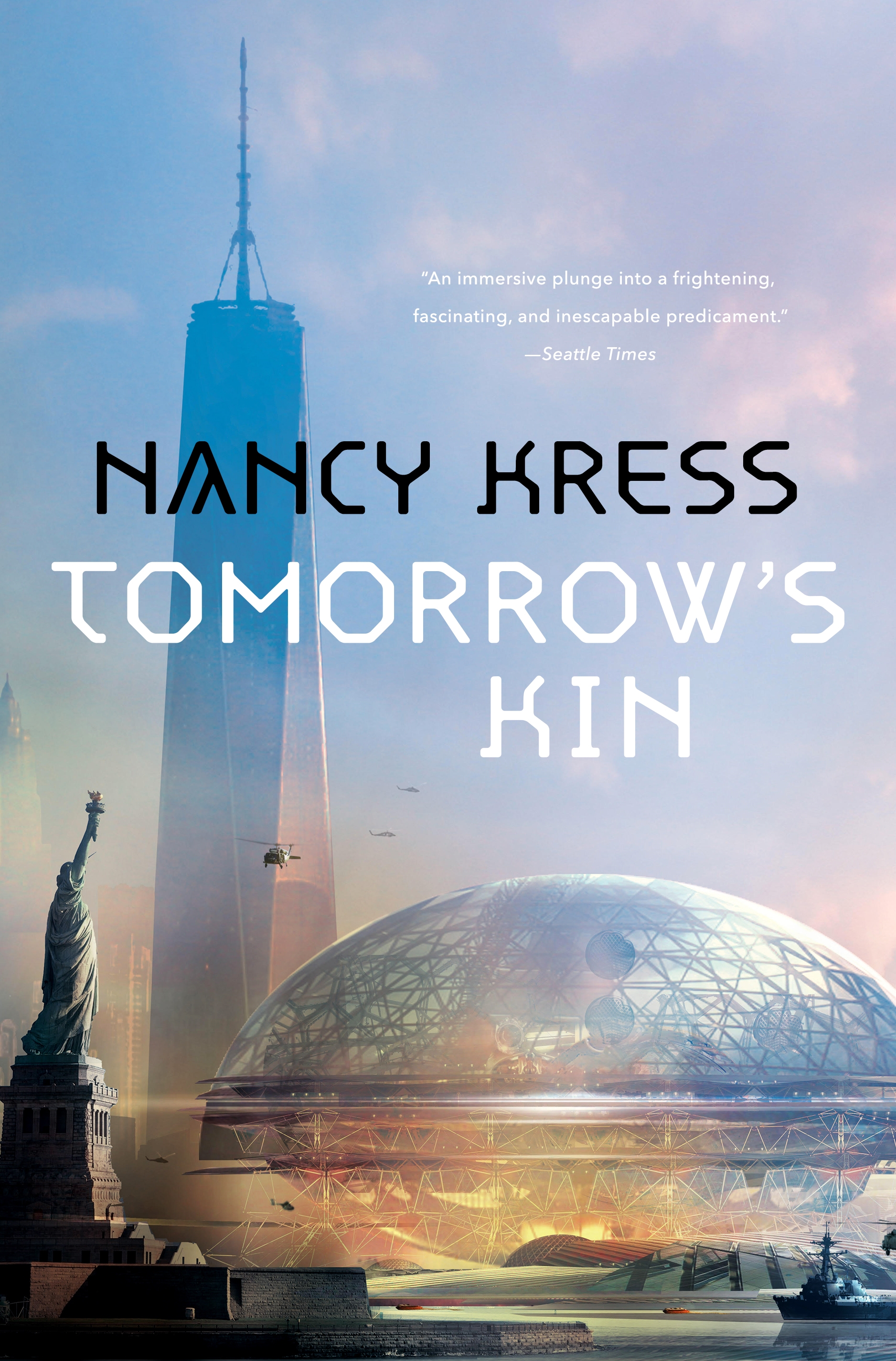

Tomorrow’s Kin is the first volume in and all new hard science fiction trilogy by Nancy Kress based on the Nebula Award-winning Yesterday’s Kin.

The aliens have arrived… they’ve landed their Embassy ship on a platform in New York Harbor, and will only speak with the United Nations. They say that their world is so different from Earth, in terms of gravity and atmosphere, that they cannot leave their ship. The population of Earth has erupted in fear and speculation.

One day Dr. Marianne Jenner, an obscure scientist working with the human genome, receives an invitation that she cannot refuse. The Secret Service arrives at her college to escort her to New York, for she has been invited, along with the Secretary General of the UN and a few other ambassadors, to visit the alien Embassy.

The truth is about to be revealed. Earth’s most elite scientists have ten months to prevent a disaster—and not everyone is willing to wait.

What’s Nancy’s favorite bit?

NANCY KRESS

When I ask the writers I know if they like their early published work, I get various answers. Some do; some don’t; some wince. I’m a wincer about at least three of my earliest novels. When fans at conventions bring me the worst of them to be signed, I write on the flyleaf, “Please read something else!”

All of which points up the fact that over time, tastes change. Mine, yours, the reading public’s. I liked my dreadful book (and no, I’m not saying which one it is) when I wrote it, decades ago. Tastes in characters change, too. Once, until she became a cliched joke, “the scientist’s beautiful daughter” was a mainstay of SF. So was the comic minority sidekick and the rock-jawed starship captain.

What is now fashionable—even obligatory—is the kick-ass heroine. Katniss Everdean. Rey in Star Wars. Arya Stark. Breq of Ancillary Justice. Furiosa. Wonder Woman. And practically every single story I see from writing students when I teach. The kick-ass heroine is admirable. I admire her. She fights with swords or bows or finely honed martial arts. She commands magic. She defeats oppressors, saves medieval kingdoms and interplanetary empires, annihilates anyone stupid enough to lay a hand on her.

My protagonist is not a kick-ass heroine.

Marianne Jenner, of my new novel Tomorrow’s Kin (Tor), is smart, persistent, idealistic. She is also in late middle-age, has never been in a physical fight in her life, does not own a weapon and doesn’t want to. At the first whiff of danger, she sensibly hires a bodyguard. Scientist, grandmother, social activist, she is a sexual being (yes, at over 50!) with sometimes terrible taste in lovers. She is made vulnerable by her love for her difficult children and gifted grandchildren. Marianne affects large events, including an epidemic, an ecological collapse, and a global war, but not from carrying out a grand design. She has no grand design. She does the best she can with the various messes she finds, some of which she created herself. Like most of the rest of us, much of the time.

Marianne isn’t, of course, the only major character in the novel, which extends the story of my Nebula-winning novella “Yesterday’s Kin” ten more years. There is Jonah Stubbs, the colorful and profane entrepreneur of a privately built starship. There is Colin, five years old and able to hear in untrasonic and infrasonic ranges inaudible to “normal” humans. There is Sissy, exuberant assistant to Marianne, and her handsome, weapons-expert boyfriend, Tim. There are scientists trying to build a starship from alien physics, Americans bent on mayhem, and Russians bent on revenge. There are a very lot of dead mice, the result of an unexpected and disastrous ecological collapse. Here is Marianne, waiting to go on stage to give a pro-space speech:

Marianne stood in a small storage room somewhere in the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center at the University of Notre Dame, waiting to go on stage and staring at eight mice.

They were, of course, dead. These eight, however, looked unnervingly lifelike, superb examples of the taxidermist’s art. Why were they here, meeting her gaze with their shiny lifeless eyes from behind the glass of a tiered display case? Had they been moved to this unlikely venue from another building, to sit among cardboard cartons and discouraged-looking mops, because someone could no longer bear to be reminded of what had been lost?

Sissy Tate, Marianne’s assistant, stuck her head into the room. “Ten minutes, Marianne. Are those mice? Wow, it’s stuffy in here.”

“No windows. What about the—”

“They should have put you in the green room! Or at least a dressing room!” Sissy shook her frizzy cherry-red curls, which leaped around her head as if electrified. Two weeks ago the curls had been the same rich brown as her skin. Today’s sweater, purple covered with tiny mirrors, glittered.

Marianne said, “There’s a concert setting up in the big hall. No space.”

“That’s not the reason and we both know it. But at least you don’t have to worry about the storm—this one is going to miss South Bend. No problem.” Sissy’s head disappeared, and Marianne went back to contemplating mice.

Eight representatives of what had been the world’s most common herbivore, now existing nowhere in the world except for a few sealed labs.

Mus musculus and Mus domesticus, their pointed snouts and scaly tails familiar to anyone who ever baited a mousetrap or worked in a laboratory.

A deer mouse and a white-footed mouse, almost twins, looking like refugees from a Disney cartoon.

On the second glass shelf, the shaggy, short-tailed meadow vole and its cousin, the woodland vole.

A bog lemming, its lips drawn back to show the grooves on its upper incisors.

And finally, a jumping mouse, looking lopsided with its huge hind feet and short forelimbs.

“Hey,” Marianne said to the jumping mouse, of which no specimens had been saved. “Sorry you’re extinct.”

“You talking to a mouse?” a deep voice said behind her.

Marianne turned to Tim. “No, I was not talking to the mice,” she said with what she hoped was dignity.

Marianne is my favorite bit.

Other older women protagonists do exist: Kij Johnson’s Velitt Boe (“The Dream-Quest of Velitt Boe”), Ursula LeGuin’s Yoss (“Betrayals”), more. But not many more. Does science fiction have room for more such protagonists: not young, female, cerebral rather than physical, armed with nothing more than intelligence and a fierce determination to influence for good, rather than to conquer for good?

I hope so.

LINKS:

BIO:

Nancy Kress is the author of thirty-three books, including twenty-six novels, four collections of short stories, and three books on writing. Her work has won six Nebulas, two Hugos, a Sturgeon, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award. Much of her work concerns genetic engineering. Kress’s fiction has been translated into Swedish, Danish, French, Italian, German, Spanish, Polish, Croatian, Chinese, Lithuanian, Romanian, Japanese, Korean, Hebrew, Russian, and Klingon, none of which she can read. In addition to writing, Kress often teaches at various venues around the country and abroad, including a visiting lectureship at the University of Leipzig and a recent writing class in Beijing. Kress lives in Seattle with her husband, writer Jack Skillingstead, and Cosette, the world’s most spoiled toy poodle.