Olivia Waite is joining us today to talk about her novel The Lady’s Guild to Celestial Mechanics. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Olivia Waite is joining us today to talk about her novel The Lady’s Guild to Celestial Mechanics. Here’s the publisher’s description:

As Lucy Muchelney watches her ex-lover’s sham of a wedding, she wishes herself anywhere else. It isn’t until she finds a letter from the Countess of Moth, looking for someone to translate a groundbreaking French astronomy text, that she knows where to go. Showing up at the Countess’ London home, she hoped to find a challenge, not a woman who takes her breath away.

Catherine St Day looks forward to a quiet widowhood once her late husband’s scientific legacy is fulfilled. She expected to hand off the translation and wash her hands of the project—instead, she is intrigued by the young woman who turns up at her door, begging to be allowed to do the work, and she agrees to let Lucy stay. But as Catherine finds herself longing for Lucy, everything she believes about herself and her life is tested.

While Lucy spends her days interpreting the complicated French text, she spends her nights falling in love with the alluring Catherine. But sabotage and old wounds threaten to sever the threads that bind them. Can Lucy and Catherine find the strength to stay together or are they doomed to be star-crossed lovers?

What’s Olivia’s favorite bit?

OLIVIA WAITE

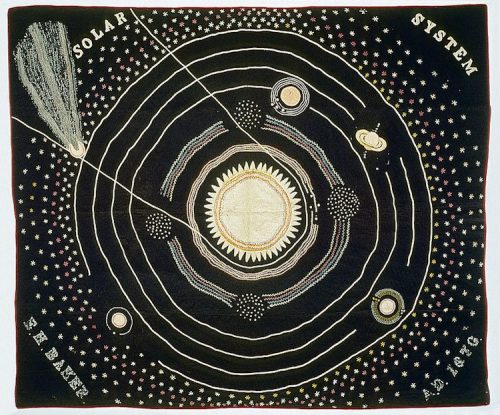

In 1876 a woman in Iowa named Ellen Harding Baker finished a solar system quilt. Ellen was a teacher and an astronomer, and in her lectures she used her quilt as a visual aid: it’s made of wool and silk in mostly black and white, with details of red and gold and blue. The quilt-top shows the sun and a dazzling comet and the orbits of all eight planets (this was before there were nine, and long before we went back down to eight).

In 2018, I wanted to write a book about a lady astronomer who falls in love with a countess who’s an accomplished embroiderer. I thought this book was going to be about Art Versus Science, Beauty Versus Truth, ladies kissing—important historical ideas like that. The story’s set in 1816, in London, and in the course of doing research I found myself wandering online archives of old cross-stitch and embroidery samplers. It’s a much, much weirder world than you expect: alongside all the happy animals and Bible verses there are samplers mourning lost loved ones and describing children dying horribly, all carefully created by putting down one tiny length of thread at a time.

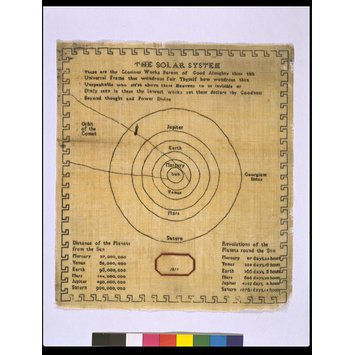

One sampler, dated 1811, was a model of the solar system.

I was gobsmacked: the pattern had been printed, which meant it had been produced for sale. That means there was enough of a market for astronomy-themed embroidery that someone had created a product to satisfy demand. This wasn’t a one-off. The sampler shows the sun and the first seven planets, including the one labeled Georgium Sidus (named for King George III, which would later be changed to Neptune so it wouldn’t feel out of place among the other mythologically named planets).

If there was a market, there might be other examples like this one. I started searching more broadly for astronomy-themed embroidery, and bam, there was Ellen Harding Baker’s quilt.

It changed everything.

Let’s talk about how much time it takes to make a quilt: a lot. Cutting fabric, top stitching, seaming. Even if you have a Singer sewing machine to help with the piecework, you still end up doing all that fine embroidery by hand. You have to really love the subject you’re working on to spend seven years illustrating it.

You also have to believe your subject can be beautiful. You have to believe that loveliness is a kind of fact—and that showing the solar system’s aesthetic appeal is an important part of describing it accurately.

Ellen Harding Baker was doing Art and Science, Truth and Beauty. I realized my entire framework had been flawed—and not just about the book. As a feminist and that annoyingly precocious kid who loved school and learning and tests and all that, I always felt like I had failed on some level because I hadn’t ended up a scientist in a prestigious field in need of more women. I’d been quietly, thoughtlessly buying into notions of hard science versus soft humanities, logical manly knowledge versus flimsy feminine imagination. These categories were painfully, uselessly limiting, and I promptly spent the entire romance letting my fictional ladies knock them down bit by bit to see if we couldn’t create something better.

I put in something like the sampler—but I had to leave out Ellen Baker Harding and her quilt. She lived sixty years later and on a different continent; there was no way I could work it into the text.

But it’s still my favorite bit, because even though it’s not anywhere on the page, it shaped everything that I put into the book. It’s the heart of the entire 80,000-word idea.

Ellen Harding Baker died before she reached forty, so the seven years she spent making her quilt turned out to be nearly a quarter of her entire life. And unlike the unknown young lady who stitched the 1811 sampler, she signed it. Sewed her name and the date and the words Solar System right onto the wool, in all caps, so there would be no denying what it was, who made it, and when.

That we have her quilt and know her name is rare, especially since museum collections and historical narratives so often lean toward masculine-coded ideas of what objects and events are important: battles and discoveries and conquest, political power and violence. We keep swords and armor and royal portraits; we consign kitchenware and cast-off clothes to the trash bins of memory.

Writers often think of research as a kind of collection: you gather up facts and trivia and people until you can lay them all out for admiration like specimens in a curio cabinet. But with this book, I’ve realized there’s another method, which needs another metaphor. Imagine a writer’s mind as a space where story-bits accumulate, piling up in great formless heaps like fresh snowbanks. Inspiration is the thing that comes along and leaves an impression—the muse that tumbles full-length into the snow, waving arms and legs for a snow angel, imposing a shape on all that nebulous story-stuff. Inspiration moves on: you don’t need to keep it or trap it or put pins through its fragile wings.

What matters is the impression it left behind, that space in which we find meaning. So I thought of Ellen Harding Baker and wrote about the affinity between art and science, and how the truth could be beautiful. I wrote about artificial categories, and how to not let them keep you from pursuing better ideas.

All that, and ladies kissing, too. It’s the best and the truest writing I’ve ever done.

LINKS:

A Lady’s Guide to Celestial Mechanics Universal Book Link

BIO:

Olivia Waite writes historical romance, fantasy, and science fiction. She is also the monthly romance columnist for the Seattle Review of Books, where she writes reviews of romances old and new and thoughtful essays on the genre’s history and future.