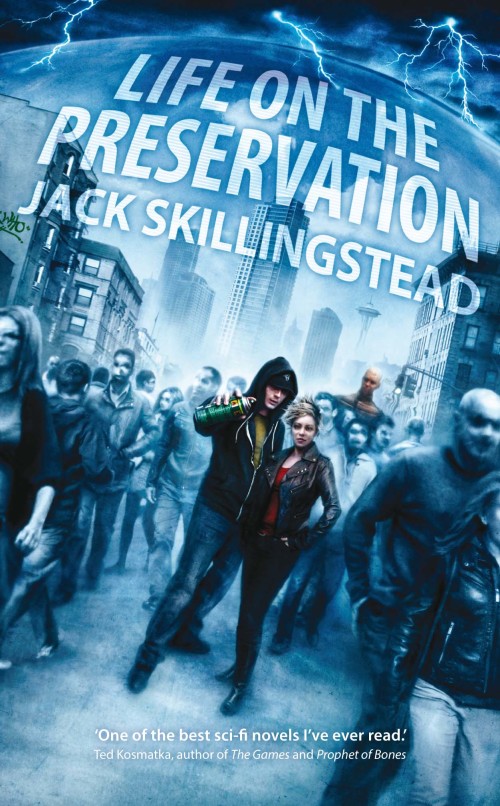

Here’s one of my favorite people with a new novel, Life on the Preservation. For those of you who are interested in process, Jack talks about how he expanded the short story into a novel

Inside the Seattle Preservation Dome it’s always the Fifth of October, the city caught in an endless time loop. ‘Reformed’ graffiti artist Ian Palmer is the only one who knows the truth, and he is desperate to wake up the rest of the city before the alien Curator of the human museum erases Ian’s identity forever. Outside the Dome, the world lies in apocalyptic ruin.

Small town teenager Kylie is the only survivor to escape both the initial shock wave and the effects of the poison rains that follow. Now she must make her way across the blasted lands pursued by a mad priest and menaced by skin-and-bone things that might once have been human. Her destination is the Preservation, and her mission is to destroy it. But once inside, she meets Ian, and together they discover that Preservation reality is even stranger than it already appears.

JACK SKILLINGSTEAD

Almost five years ago, when I first thought I’d like to expand my short story, “Life on The Preservation,” into a novel, it struck me as an opportunity to write a deliberately commercial story of the alien-invaders-vs-plucky-survivors type. The story had, in my mind, at least, a wonderful hook: For unknown reasons of their own, aliens lay waste to planet Earth but preserve various representative environments as living, fully interactive museums. For instance, under one such Preservation Dome the city of Seattle, complete with a living population ignorant of their predicament, endlessly repeats the last day before world destruction. Into this situation the plucky survivors send the one member of their band still young and healthy enough to take on the job of penetrating the Dome — a seventeen year old girl named Kylie. Once Inside the Seattle Dome she dodges alien tourists and struggles to resist the illusion of a city aloof from the violence and poisons of the outside world Kylie has known all her life. Then, before she can complete her mission, she meets a boy, falls in love, and must decide whether to carry on with her duty or stay and become trapped herself, a new member of the endlessly repeating Day.

The short story version of this tale had already proved somewhat popular with readers of Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, as well as editors of two Year’s Best anthologies. But a strange thing happened when I sat down to write the novel.

It refused to cooperate.

As I wrote draft after draft, trying to force my story into the structure I thought it must inhabit I gradually had to admit that I didn’t give a damn about the plucky survivors — and, worse, I didn’t believe in them, or in the relevance of Kylie’s mission. What worked at five thousand words simply would not translate to ninety thousand. The book withered under my furiously typing fingers. After eighteen months of steady work, I was about to lose my story.

Out of some kind of desperation I started over, virtually from scratch. I kept the basic situation but discarded all my preconceived ideas about structure and intent. If “Life On The Preservation” was going to have a chance to live, it would have to evolve in its own way. This was a hard lesson I had learned long ago, in relation to writing short fiction. By forcing my story into a preconceived pattern of rising tension I had walled out the most important element in any writer’s toolbox: the element of the unexpected, which inevitably leads to the heart of the story.

Writing this way is like pushing off from shore and hoping you can build a couple of oars before the current takes you over the falls. It’s scary and exhilarating and chaotic. Some times you do go over the falls, and what’s left is unrecoverable. But often enough you manage to reach the far shore, where you drag your boat onto the sand and begin to figure out what you just did. Or, to switch metaphors in midstream, now it’s time to draw the map of where you’ve been. Drawing of said map after the fact is a huge pain in the neck, requiring rewrites, deletions, additions — and just generally a lot of hard thinking. Some writers are able to draw the map ahead of time, and I envy and admire them for it. They can see where they need to go before they go there, and their maps are largely the same at the end of the book as they were at the start.

It took me another two years to finish “Life On The Preservation.” In this business, four years between books is a life time. On the plus side, I did indeed discover the secret heart of my novel: Vanessa Palmer. She is the older sister of my male lead, Ian. She did not figure in any of the earlier structured drafts, only emerging when I needed her to emerge, because the story had veered in an unanticipated direction that required the services of a hypnotherapist. Vanessa is very much like my own sister, of course. Much older than Ian, with a past troubled by mental illness, a woman who finally landed on solid ground. She’s not my sister, but she wouldn’t exist without my sister’s influence informing her life and motivation — and she is my favorite bit in “Life On The Preservation,” Vanessa Palmer and the wounded relationship between her and Ian.

RELEVANT LINKS

Life on the Preservation amazon | B&N

BIO

In 2001 Jack Skillingstead won Stephen Kings “On Writing” competition. Two years later his first professional sale appeared in Asimov’s. “Dead Worlds” was a Sturgeon Award finalist and was reprinted Dozois’s Year’s Best SF. Since then Jack has pubilshed more than thirty stories in professional markets, two novels and a short story collection. He lives in Seattle with his wife, writer Nancy Kress.

Ok, I’m sold. I just ordered a copy.