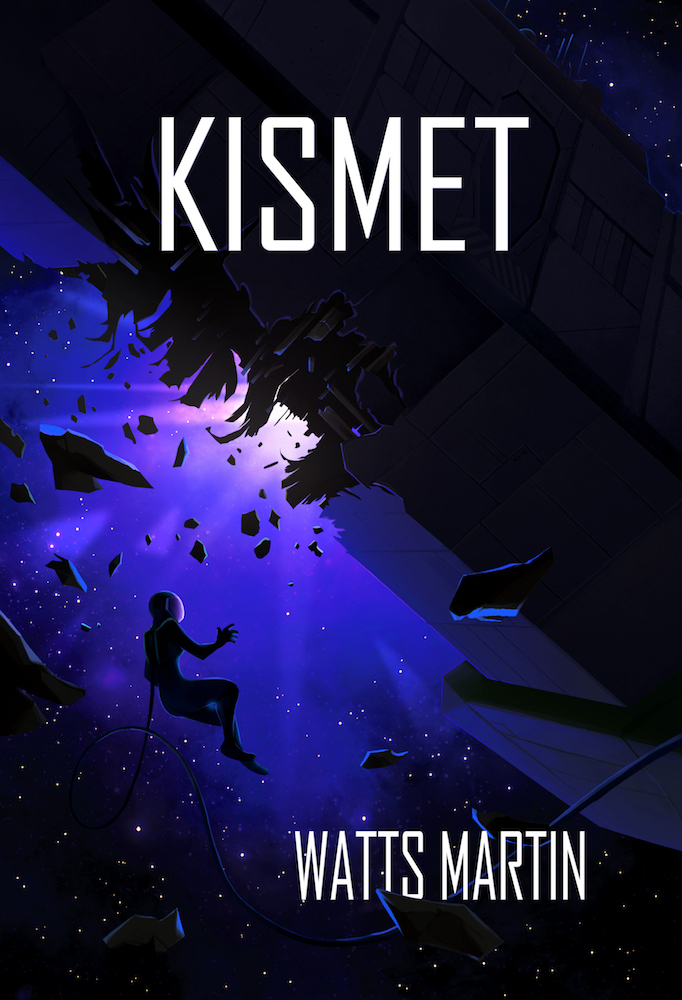

Watts Martin is joining us today with his novel Kismet. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Watts Martin is joining us today with his novel Kismet. Here’s the publisher’s description:

The River: a hodgepodge of arcologies and platforms in a band around Ceres full of dreamers, utopians, corporatists and transformed humans, from those with simple biomods to the exotic alien xenos and the totemics, remade with animal aspects. Gail Simmons, an itinerant salvor living aboard her ship Kismet, has docked everywhere totemics like her are welcome…and a few places they’re not.

But when she’s accused of stealing a databox from a mysterious wreck, Gail lands in the crosshairs of corporations, governments and anti-totemic terrorists. Finding the real thieves is the easy part. To get her life back, Gail will have to face her past and what’s at stake may be more than just her future.

What’s Watts’s favorite bit?

WATTS MARTIN

A few years back, I didn’t have a novel. I had a muddle of ideas, a main character I was in love with, and a disjointed plot that could maybe stretch into a novella. Even so, it got me into an intensive SF novel writing workshop at the University of Kansas.

Among the notes I scribbled during sessions was this suggestion: one of my story’s motifs was “embodiment.” It wasn’t until I got home that I stopped, read that a few times, and thought: wait, what the hell does that mean?

In the future of Kismet, some humans are “transform,” visibly bioengineered in some fashion. A subset are “totemics,” adapting animal aspects ranging from (relatively) subtle tweaks like ears and tails to full-body makeovers. Totemics are a minority even on “The River,” a section of frontier space around Ceres. But in a solar system with a population of ten or eleven billion, that’s still in the millions.

Okay: so what do totemics embody? Animal and human. Technology and nature. A radical, extreme statement that the future lies in unification rather than dominion. At least, that’s the answer Mara, the original totemic, would give. But someone else might have a different answer: spiritual belief, xenophiliac aesthetics, a sense you’re more you when your nature isn’t the one you came into the world with. Gail, the book’s protagonist, would wryly add, “Because your transform parents wanted a transform kid.” She’s comfortable looking like a rat, but it’s not like she aspired to it.

There’s a scene near the middle of Kismet when two side characters discuss Mara’s dream—and the dream of many totemics, including Gail’s mother and sister—of transformations becoming inheritable, a goal that’s always stayed just out of reach. Gail’s adopted (and estranged) sister Sky, like their mother, remains deeply committed to that hope. But her friend Ansel, another totemic, shocks Sky by taking a fierce stand against it. On the surface, their disagreement is political, the more libertarian Ansel offended by Sky’s socialism. But there’s more to it than that. “Totemics have gotten along fine since before The River existed,” he argues. “We’ll keep getting along just fine choosing whether to transform ourselves or our children.”

What I love about this exchange is that their debate is both universal and unique to a science fiction context. There are parallels to our world and time, but transform and cisform don’t quite map to transgender and cisgender, let alone race, orientation or religion. Yet that debate in their society hinges on what makes identity so complicated. It’s a mix of what we’re assigned through the circumstances of our birth and what we choose. We embrace parts of the identity we came into the world with and reject others. We choose new elements for our identity, adding new bits, filling holes, and when we must, making drastic changes. If the goal of inheritable transformation arrives for the totemics, they’ll gain something immeasurable—at the cost of shifting a core part of their identity from choice to assignment.

I hadn’t realized their exchange was about the story’s underlying theme until well after I’d written it. But your characters often know more about your story than you do, don’t they? I didn’t know what “embodiment” meant at first. Ansel and Sky—and Gail—got it immediately.

A small confession: it’s tough to point to this one exchange and say it’s my absolute favorite bit from the story. The novel is, after all, about Gail, not Ansel or Sky. But this moment turns out not to only be a reflection of the story’s theme, but a signpost for Gail’s own journey. Until the morning this conversation takes place, her real interest had been getting back to a life of minimal responsibility. But as she comes to terms with her mother’s death—and her complicated relationship with Sky—she’s realizing she has big choices to make. And, even though she doesn’t see it yet, she’s already started making them.

LINKS:

BIO:

Watts Martin is the author of several fantasy novellas including Cóyotl Award winner Indigo Rain and nominee Going Concerns, and a host of short stories in small press anthologies including Inhuman Acts, Five Fortunes and The Furry Future. Watts grew up around Tampa Bay, Florida, and now lives in Silicon Valley, primarily working as a technical writer.