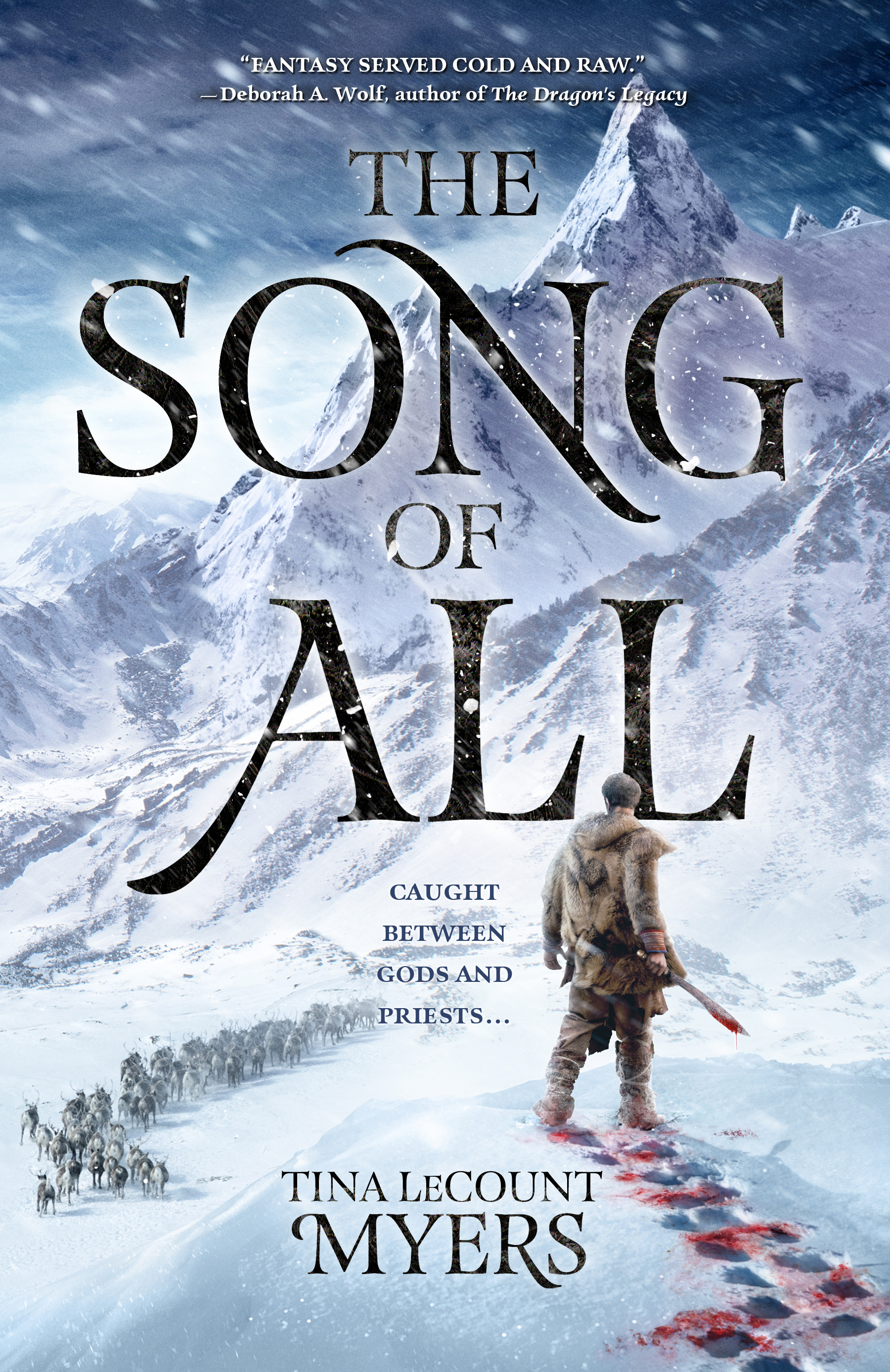

Tina LeCount Myers is joining us today with her novel The Song of All. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Tina LeCount Myers is joining us today with her novel The Song of All. Here’s the publisher’s description:

On the forbidding fringes of the tundra, where years are marked by seasons of snow, humans war with immortals in the name of their shared gods. Irjan, a human warrior, is ruthless and lethal, a legend among the Brethren of Hunters. But even legends grow tired and disillusioned.

Scarred and weary of bloodshed, Irjan turns his back on his oath and his calling to hide away and live a peaceful life as a farmer, husband, and father. But his past is not so easily left behind. When an ambitious village priest conspires with the vengeful comrades Irjan has forsaken, the fragile peace in the Northlands of Davvieana is at stake.

His bloody past revealed, Irjan’s present unravels as he faces an ultimatum: return to hunt the immortals or lose his child. But with his son’s life hanging in the balance, as Irjan follows the tracks through the dark and desolate snow-covered forests, it is not death he searches for, but life.

What’s Tina’s favorite bit?

TINA LECOUNT MYERS

One of my favorite parts of my fantasy novel is the science behind it. In fact, I started writing The Song of All after a debate with my husband about what distinguishes science fiction from fantasy. Let’s just say it was a robust discussion in which my husband made the point that science fiction presents what is possible based on science, while fantasy presents magic and the supernatural and is not based on science, a distinction I took umbrage with.

“What about quantum physics?” I asked. “What about dark matter and dark energy? Couldn’t they explain magic and metaphysical elements?”

“Fine,” he conceded, knowing I had watched more TedX and Neil deGrasse Tyson talks on YouTube than he had. “But there are no such things as elves.”

“But there could be,” I said.

Human evolution, even starting as late as Homo erectus, reflects substantial differences in morphology. Comparing Homo sapiens to the Neanderthals, Homo sapiens have keener eyesight, hearing, and sense of smell. Through natural selection, any number of potential phenotypes might evolve if those individuals are successful at surviving and passing on their genetics. Nothing precludes the evolution of an “elf.”

Later, as I rehashed the argument, I thought about how many cultures have elves as part of their mythology. I recalled the Finnish folktales my own grandparents told me as a child about spirits that lived in the far north, in Saamiland. I began to imagine just how these magical creatures might have evolved. And what started as research to prove my point unexpectedly ended up as a fantasy novel.

In The Song of All, the Jápmemeahttun (pronounced yahp.meh.mehah.toon) are my “elves.” They are distinct from the human Olmmoš (pronounced ol.mow.sh), having evolved over millennia of prehistory in isolation. While the two species have similar morphology, the Jápmemeahttun have developed some distinctive characteristics due to environmental and social pressures. One such characteristic is their unusual reproductive system. The Jápmemeahttun are protogyny sequential hermaphrodites, meaning they change sexes, in this case from female to male, a model that I borrowed from real life biological sciences.

Researchers suggest that sequential hermaphroditism occurs in nature when an individual animal reproduces most efficiently as one sex when younger, but as the other sex when older. Among invertebrates and vertebrates, there are many examples of sequential hermaphroditism, both protogyny (female to male) and protandry (male to female). The Clownfish switches from male to female. The Blackfin Goby fish can go both ways depending on need. The European common brown frog sometimes switches from female to male when the females are older, prolonging their lifetime reproductive success. But my favorite example is the wrasse because of the impassioned lecture my college biology professor gave on this fish.

After weeks of stunningly dry lectures, my introductory biology course had finally evolved from the cellular level to the topic of reproduction. My professor, who for those proceeding weeks had shown little enthusiasm for the material, began to explain with surprising animation the mating rituals of this small fish-the wrasse. With gusto, she described how when the dominant male of a school dies or as she put it “goes out for a cup of coffee”, the largest female will begin seducing the other females and develop male organs to become dominant in the school. She concluded with a cackle that, “There’s a reason why they’re called Sneaky Suckers.” Only she did not say Suckers.

Struck by my professor’s unexpected liveliness, I stopped taking notes and saw for the first time just how mind-blowing biological adaptations can be. Two decades later, when I started to write The Song of All, I remembered that moment of wonder and saw in evolution the possibility to write about magical creatures, using not only imagination, but also science to shape them.

As a species, the Jápmemeahttun are far more honorable in their courtship than the wrasse. They do not rely on duplicity to ensure that dominant genes are passed on. But like the wrasse, the Jápmemeahttun, as I envisioned them, are the result of natural selection. They adapted in response to their imagined world, just as species have on this planet. Evolution has created some pretty magical creatures in the Earth’s 4.5 billion years of existence: Pterodactyls, Duck-billed Platypuses, Human Beings. And numerous cultures acknowledge the existence of unseen supernatural beings. So, while I am willing to concede to the point that there is no scientific evidence of elves, I add the caveat, “Not yet.”

LINKS:

The Song of All Universal Book Link

BIO:

Tina LeCount Myers is a writer, artist, independent historian, and surfer. Born in Mexico to expat-bohemian parents, she grew up on Southern California tennis courts with a prophecy hanging over her head; her parents hoped she’d one day be an author. The Song of All is her debut novel.