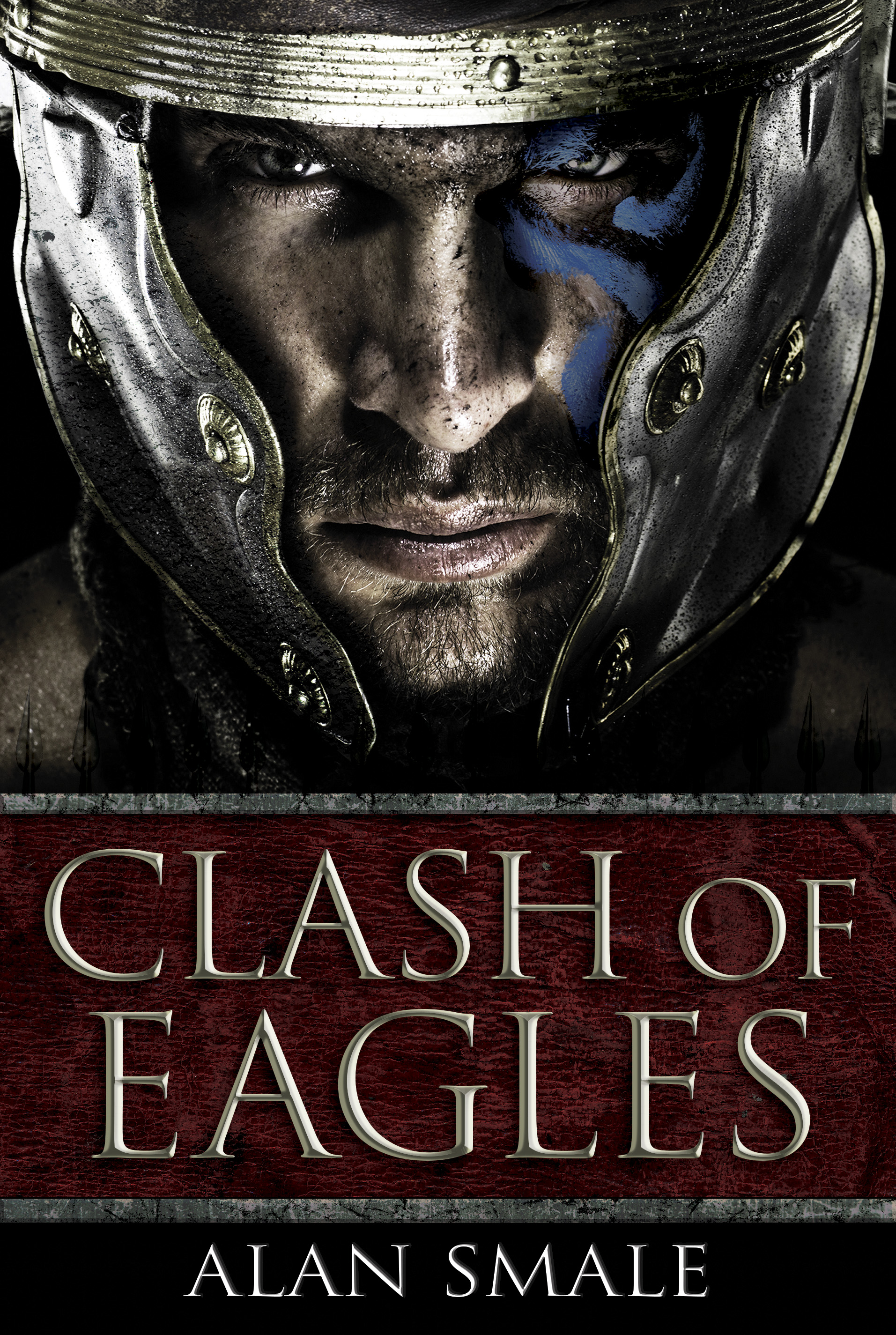

Alan Smale is joining us today with his novel Clash of Eagles. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Alan Smale is joining us today with his novel Clash of Eagles. Here’s the publisher’s description:

Perfect for fans of military and historical fiction—including novels by such authors as Bernard Cornwell, Naomi Novik, and Harry Turtledove—this stunning work of alternate history imagines a world in which the Roman Empire has not fallen and the North American continent has just been discovered. In the year 1218 AD, transported by Norse longboats, a Roman legion crosses the great ocean, enters an endless wilderness, and faces a cataclysmic clash of warriors, worlds, and gods.

Ever hungry for land and gold, the Emperor has sent Praetor Gaius Marcellinus and the 33rd Roman Legion into the newly discovered lands of North America. Marcellinus and his men expect easy victory over the native inhabitants, but on the shores of a vast river the Legion clashes with a unique civilization armed with weapons and strategies no Roman has ever imagined.

Forced to watch his vaunted force massacred by a surprisingly tenacious enemy, Marcellinus is spared by his captors and kept alive for his military knowledge. As he recovers and learns more about these proud people, he can’t help but be drawn into their society, forming an uneasy friendship with the denizens of the city-state of Cahokia. But threats—both Roman and Native—promise to assail his newfound kin, and Marcellinus will struggle to keep the peace while the rest of the continent surges toward certain conflict.

What’s Alan’s favorite bit?

ALAN SMALE

I’m happy to say that it took me a while to decide. After all, I’ve had my head in the world of Clash for many years now: Clash of Eagles was a novella before it was a novel, and then it became a trilogy, and then it sold to Del Rey, and today it finally gets its coming-out party. My favorite location is easy: it’s the ancient city of Cahokia, the great pre-Columbian metropolis on the banks of the Mississippi, close to where St. Louis stands today. Cahokia covered over five square miles and contained at least 120 mounds of packed earth and clay, some of them colossal. Some 20,000 people lived there, meaning that in our world in thirteenth century Cahokia was larger than London, and no city in northern America would be larger until the 1800s. It was a major hub of the Mississippian culture for several hundred years. Trying to bring Cahokia to life as a vibrant setting, as true to the archeological evidence as possible but inhabited by realistic, down-to-earth people, was one of the great joys of writing the book.

I also got a kick out of writing the battle scenes. When I’m reading history or SF novels I sometimes feel distanced by set piece battle scenes – and action scenes in general – because suddenly the narrative is all about the action and the tactics instead of the characters. I’ve skimmed many a battle scene in my reading life. I didn’t want anyone to skim mine, so I’ve done my level best to keep the conflicts intimately connected to the characters in the thick of them.

Ultimately, though, the scene that means the most to me is a calmer moment. After much blood and thunder and character-infused derring-do, my hero Gaius Marcellinus finds himself stranded in Cahokia. He is wounded, confused, isolated, guilty at the deaths he is responsible for, and – of course – speaks no Cahokian. The paramount chief, Great Sun Man, assigns three children to learn his language; in Nova Hesperia – my version of North America – children often help translate between the multitudes of tongues and dialects. This does not immediately go well, because

Marcellinus had no particular affinity for children; he had stopped talking to them at roughly the time he had stopped being one himself. He had treated his own daughter, Vestilia, like an adult from the time she was six.

The children are Tahtay, eleven winters old; Kimimela, eight winters; and my sneaking favorite–

The smallest of the three was called Enopay, which meant “bold” or “brave” or “defiant” or some other idea synonymous with standing up straight and strutting around with his fists up, and none of the three knew how old Enopay might be.

And away they go:

After that the work began in earnest, with Tahtay miming an action or an idea, saying a word, and then inviting Marcellinus to say the word in his own tongue. Their young brains soaked up his Latin like sponges.

Their efforts to teach him spoken Cahokian in return were an abject failure. Marcellinus could hold a Cahokian word in his mind only until Tahtay said something else, and then the first word slid out of his head as if it had never been there. He did much better with the gestural language, the hand-talk as Kimimela called it, because the gestures had their own logic; the sign for water involved pretending to drink from your cupped hand, sleep had him resting his cheek against his hands, and the sign for question—the most useful gesture of all and one he used constantly—required him to hold up his hand with his fingers open and waggle it at the wrist.

Even so, by noon Marcellinus was wearying of the effort, and the weight of his guilt was growing inside him once again. He swallowed the last of the chewy hazelnut cakes they had brought him, raised his hands in surrender, and stood.

“Hand-talk,” Tahtay said sternly in barely comprehensible Latin. “Sit, hand-talk hand-talk.”

Marcellinus swung his hand back and forth in the gesture for No and then gestured Walk, graves.

“Walk to river,” Enopay counteroffered in Latin.

Walk graves, then walk river, signed Marcellinus.

Kimimela grimaced and gestured No. “Kimi hit food,” she said aloud.

“What?” Marcellinus said, and knocked twice on his right forearm with his left fist, which was the sign they had developed for when someone needed a definition.

Enopay mimed it. Kimimela, seeing what he was doing, mimed the same thing faster, as if competing or trying to catch up. “Huh,” said Tahtay, a grunt he had picked up from Marcellinus.

Marcellinus thought he understood. He pointed to Enopay’s arms. “Grind?” He pointed to the space beneath. “Corn?” He mimed eating to try to confirm it.

“Kimimela grind corn. No walk graves, grind corn,” said the girl.

“That’s quite a lot of Latin for one day,” Marcellinus said.

“Hand-talk!”

Marcellinus stood. The inactivity had rendered his leg muscles almost immobile. He tried not to let the children see how stiff and weary he was, wondering what the word for pride was. “Enopay,” probably.

For obvious reasons, speculative fiction writers tend to take short-cuts with language; in many books and movies the lead characters magically become fluent within weeks of their arrival in a new land. I wanted to try something more believable, and enjoyed the challenge of doing so without bogging the story down. I think it also helps to make Marcellinus’s isolation and lack of understanding of Cahokian culture more interesting and credible.

Tahtay, Kimimela, and Enopay guide Marcellinus’s path into Cahokian culture, and play significant roles in the plot – much more significant than I’d originally intended. Their growth as human beings and, eventually, co-protagonists continues to be a fun part of writing the second and third books in the series.

And that’s my favorite bit. Thanks, Mary, for letting me talk about it!

LINKS:

BIO:

Alan Smale grew up in Yorkshire, England, and now lives in the Washington, D.C., area. By day he works at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center as a professional astronomer, studying black holes, neutron stars, and other bizarre celestial objects. However, too many family vacations at Hadrian’s Wall in his formative years plus a couple of degrees from Oxford took their toll, steering his writing toward alternate, secret, and generally twisted history. He has sold numerous short stories to magazines including Asimov’s and Realms of Fantasy, and the novella version of Clash of Eagles won the 2010 Sidewise Award for Alternate History.