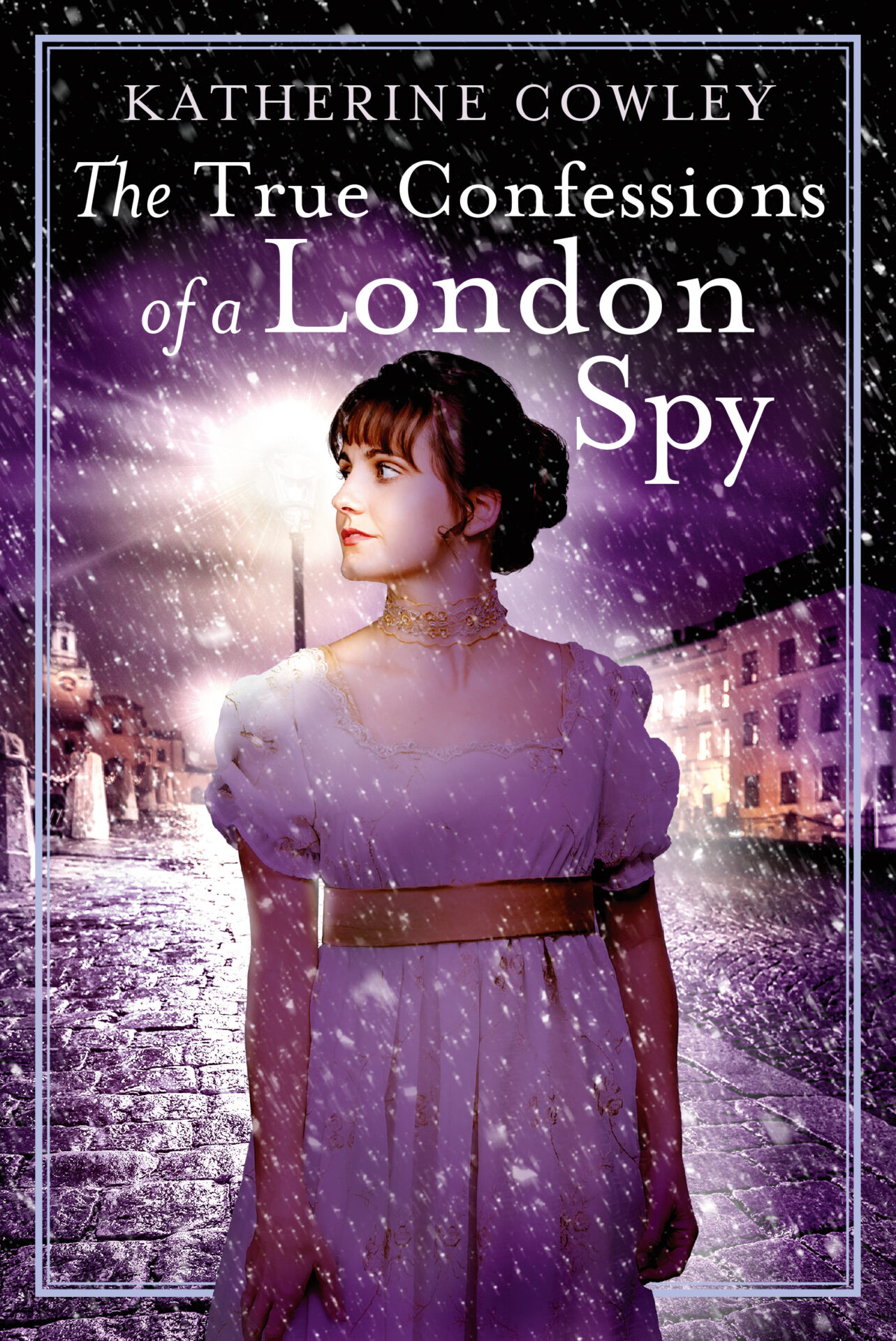

Katherine Cowley is joining us today to talk about her novel, The True Confessions of a London Spy. Here’s the publisher’s description:

No one said being a spy for the British government would be easy.

When Miss Mary Bennet is assigned to London for the Season, extravagant balls and eligible men are the least of her worries. A government messenger has been murdered and suspicion falls on the Radicals, who may be destabilizing the government in order to compel England down the bloody path of the French Revolution.

Working with her fellow spies, Mr. William Stanley and Miss Fanny Cramer, Mary must investigate without raising the suspicions of her family, rescue her friend Miss Georgiana Darcy from a suitor scandal, and solve the mystery before anyone else is harmed—all without being discovered, lest she be exiled back to the countryside.

This is the perfect job for a woman who exists in the background. Can Mary prove herself, or will this assignment be her last?

What’s Katherine’s favorite bit?

KATHERINE COWLEY

I have always loved the details of history, the fascinating tidbits that surprise and make the past come alive—like the fact that in January of 1814, the road from Dover to London was covered in 10 feet of snow and over 300 men were hired to shovel it.

During my early stages of writing The True Confessions of a London Spy, I read Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Calculating Stars, and I loved the newspaper epigraphs she included at the start of each chapter. These epigraphs provided context and created subtext, added insight and different perspectives, constructed a parallel narrative, and showed how the story world interacted with the larger one. Inspired by Mary Robinette’s novel, I decided to include a newspaper epigraph at the start of each of my chapters.

I bought a subscription to the British Newspaper Archives and used my university library account to access the archive for The Times, and I immersed myself in newspapers from January and February of 1814. I read dozens and dozens of newspapers from across different cities in England, each with different perspectives and ideologies. I read the advertisements, the articles, the letter extracts, the opinion pieces, and the pronouncements which Napoleon Bonaparte made on the continent which were translated to English and reprinted.

Reading these newspapers became my favorite bit of the writing process.

Some of my favorite articles became epigraphs for my chapters, including this one from The St. James’s Chronicle, printed in London on February 12, 1814:

“Extract of a letter from Captain Lyle:—‘I have brought home with me, at this time, a female sailor, who went away with the Ocean transport, of this port. She has been five years at sea before discovered, and would not have been found out then, but having accidentally fallen overboard. When taken up, she was stripped to be put to bed, at which time her sex was discovered. She belongs to Dundee, and went under the name of William Macdonald.’”

Some of my favorite articles did not end up as epigraphs, but I enjoyed the excuse to read them all the same.

The Sun had a regular column on female fashion. Here’s their advice from February 1, 1814:

“Female Fashions for February….Evening or Dancing Dress.—A white crape petticoat, worn over gossamer satin, ornamented at the feet with rows of puckered net, with a centre border of blue stain, or velvet, in puffs. A bodice of blue satin, with short full sleeves, and cuffs to correspond with the bottom of the dress. A full puckered border of net, or crape, round the bosom. Stomacher and belt of white satin, with pearl or diamond clasp. Hair in dishevelled curls, divided in front of the forehead, and ornamented with clusters of small variegated flowers: a large transparent Mechlin veil, thrown occasionally over the head, shading the bosom in front, and bracelets of Oriental pearl, or white cornelian. Slippers of white satin, with blue rosettes. White kid gloves; and fan of spangled crape and blue foil.”

This is an evening dress that I would personally love to own and wear. And of course, I would certainly need a lady’s maid to assist me with my hair.

The column goes on to describe a fashionable promenade or carriage costume (which includes “a Russian mantle of pale salmon-coloured cloth” and lemon-colour gloves), a dinner dress (which must be accompanied by “white velvet slippers lightly embroidered with silver in front”), and an orange boven carriage pelisse (which should be worn with a Spanish head-dress which should be “tastefully ornamented with points edged with pearl, and a superb white ostrich feather, which falls to the left side.”) Finally, it gives general advice, applicable to all women who would like to shine in February 1814 society:

“Fashionable colours for the month are orange, emerald green, light and dark fawn, ruby, purple, pale lavender, and tourquoise blue.”

I’ve seen naysayers question the historicity of the costumes in Bridgerton—shouldn’t the colors and cuts be more subdued?—yet the dresses in Bridgerton are perfectly in line with the fashion suggestions given in The Sun.

I have a soft spot for the fashion articles, but I also love those dealing with Napoleon Bonaparte. Every single day of January and February 1814, numerous articles addressed the war with Napoleon, recent battles and the movement of troops, and the existential threat posed by everything French. A few newspapers, such as Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, argued vehemently against the war.

On February 13, 1814, The Examiner spent pages exploring the nature of happiness and speculating on which of the five Bonaparte men—Napoleon and his four brothers—was likely to be the happiest.

“If [Napoleon] Bonaparte, in one of his late progresses through the streets of Paris, when he was conversing and smiling with every body, could have been met with the…question [are you happy?], what do we think would have been his answer? Perhaps one of his usual phrases, when he does not relish the dialogue—‘Pshaw! Fool—Imbecile!” and then he would have settled the matter by falling into a passion.”

The article continues its analysis, explaining that “by his continual meditations of injustice, by his secret treacheries and his open violence, [Napoleon] has involved himself in a quantity of anxieties, the very nature of which tends to diminish a man’s happiness.”

Both the British Newspaper Archive and The Times Archive have powerful search functions, but I used them only minimally. I didn’t always know exactly what sort of epigraph I needed at the start of each chapter, so I would open five or six newspapers from a given day and read, not from start to finish, but whatever drew my attention. It was like entering an art museum and instead of bringing a list of the five important pieces I needed to see, allowing myself to simply wander through, not paying attention to floor maps, but rather exploring and seeing what spoke to me. Taking this approach to newspapers enhanced my pleasure of the process and I believe resulted in better epigraphs. Reading these newspapers felt like stepping into the past, and hopefully their inclusion helps readers step into the past as well, for that is one of my favorite parts of historical fiction.

LINKS:

BIO:

Katherine Cowley read Pride and Prejudice for the first time when she was ten years old, which started a lifelong obsession with Jane Austen. She loves history, chocolate, traveling, and playing the piano, and she teaches writing classes at Western Michigan University. She lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan with her husband and three daughters. Her debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, was nominated for the Mary Higgins Clark Award.