Ed McDonald is joining us today to talk about his novel, Daughter of Redwinter. Here’s the publisher’s description:

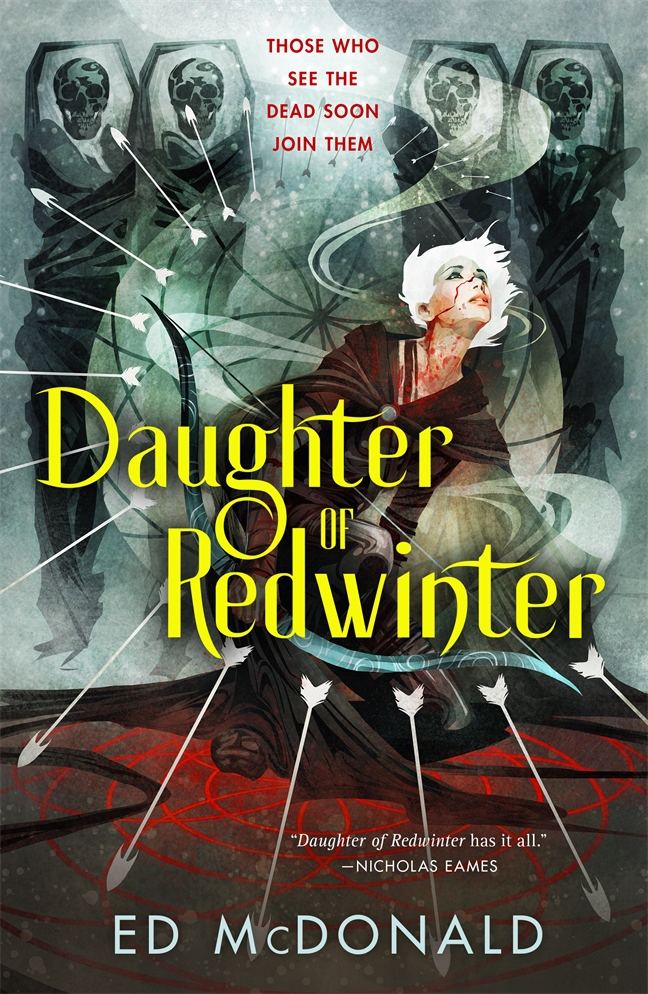

Those who see the dead soon join them.

From the author of the critically-acclaimed Blackwing trilogy comes Ed McDonald’s Daughter of Redwinter, the first of a brilliant fantasy series about how one choice can change a universe.

Raine can see–and more importantly, speak–to the dead. It’s a wretched gift with a death sentence that has her doing many dubious things to save her skin. Seeking refuge with a deluded cult is her latest bad, survival-related decision. But her rare act of kindness–rescuing an injured woman in the snow–is even worse.

Because the woman has escaped from Redwinter, the fortress-monastery of the Draoihn, warrior magicians who answer to no king and who will stop at nothing to retrieve what she’s stolen. A battle, a betrayal, and a horrific revelation forces Raine to enter Redwinter. It becomes clear that her ability might save an entire nation.

Pity she might have to die for that to happen…

What’s Ed’s favorite bit?

Ed McDonald

A whole lot of love went into writing Daughter of Redwinter. It’s a novel that combines experiences that I had through my teens, my twenties and thirties, and delivers all of it through Raine, our protagonist. And so it’s only fair that my favourite part of the book is something that comes from things I’ve learned across those decades too.

There is a part, relatively late in the story when a jealous character asks Raine:

‘Is that what you think makes a man attractive? Not a kind heart, not being supportive, not being thoughtful? It’s running aimlessly around the grounds and a pretty face.’

To which Raine replies, rather angrily and full of frustration:

‘Those aren’t things that should make you love another person. Being kind, supportive and thoughtful are the minimum level of expectation we should have for anybody.’

I grew up watching the TV sitcom Friends, and Dawson’s Creek, and they put forward what – as I have come to realise as I got older – is an uncomfortable myth. It is the notion that there is something achingly romantic about unrequited love, and that pining for someone, silently and longingly, is something that’s a normal part of existence for sensitive souled men. Even more pernicious is the idea that eventually, one grand act of selflessness will turn the entire situation on its head. Those shows told a generation of teenage boys that provided you just stuck around long enough and pined mostly in secret – but usually involving allowing all your other close acquaintances to know – that despite having no romantic interest in you, she will come around in the end.

Rachel develops feelings for Ross in a moment of realisation that he has been there, quietly, all along. Well done, Ross! You stuck in there being a decent bloke long enough that your crush’s complete lack of romantic interest in you swivelled after one big demonstration of self-sacrifice.

The older I get the more I feel that the sentiment perpetuated – which continues on in fiction today, though I feel its impact less now that I’m not a 15 year old trying to understand romance through TV – ignores the realities of how human hearts work. Unrequited love is seldom about another person; more often it’s self-absorption, and dreaming over the ideal of what that person could be. At its most toxic, it becomes a source of anger, of blaming the rest of the world for something wanted, but unreachable.

Shakespeare understood it when he wrote Romeo’s initial poetic pining for Rosaline. Romeo is crushing hard, and describes her to Benvolio: ‘Ne’er saw her match since first the world begun.’ And yet, his eye is turned within the day. His adoration of Rosaline is not based on her at all, it stems entirely from his own wish to see himself as a romantic, depressed hero. He exults in his mournful longing, because playing at feeling is powerful in its own right. But it’s a steep dark path from longing down into obsession, resentment and jealousy.

I wanted Raine to be able to speak the truth of it. I wanted her, through all the traumas she suffers and the things that she fights her way through over the course of this story, to refuse to be used as someone else’s pining post. She doesn’t exist for someone else to write sonnets about, especially someone whose view of her is more about how he sees himself than anything that really has to do with her. It’s telling perhaps that when Rachel finally ‘sees’ Ross as a viable partner, it’s seeing him aching for her as a teenager that seems to seal the deal and his years of suffering are justified.

But we don’t love just because someone is nice to us. To imagine it that way is to ignore many other vital, important factors and to reduce love and attraction to something simply achieved through behaviour that everybody should be displaying to everybody they know, all the time.

LINKS:

Daughter of Redwinter Universal Book Link

BIO:

Ed McDonald is the author of the Raven’s Mark and Redwinter Chronicles series of novels. He studied Ancient History and Archaeology at the University of Birmingham, and Medieval History at Birkbeck College, University of London. Ed is passionate about fantasy tabletop roleplay games and has studied medieval swordsmanship since 2013. He currently lives with his partner, author Catriona Ward, in London, England.