Marie Brennan’s novel A Natural History of Dragons is exactly calculated to please. It is the memoir of Lady Trent and captures the tone of memoirs from the 1800s with delightful aptitude. You know how much I adore language and this novel hits all my sweet spots, as well as offering rollicking adventures with dragons.

Marie Brennan’s novel A Natural History of Dragons is exactly calculated to please. It is the memoir of Lady Trent and captures the tone of memoirs from the 1800s with delightful aptitude. You know how much I adore language and this novel hits all my sweet spots, as well as offering rollicking adventures with dragons.

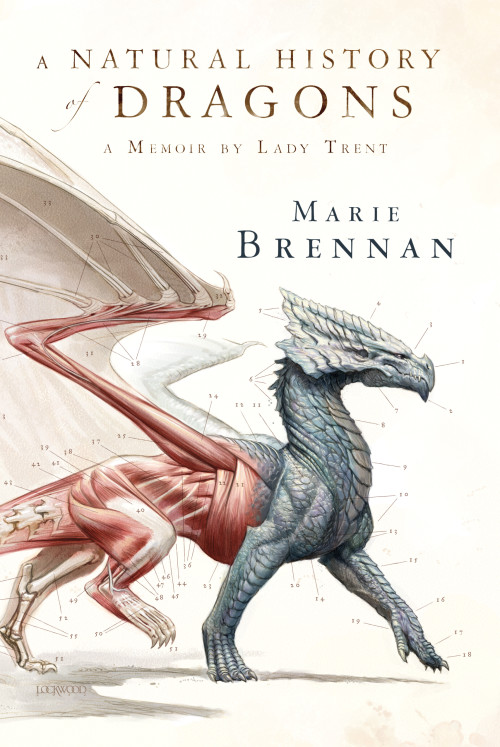

Oh, and did I mention that it is illustrated? Mmm…

What’s Marie’s Favorite Bit?

MARIE BRENNAN

When I set out to write the Memoirs of Lady Trent, I knew I wanted two main ingredients in the stew: natural history (specifically as applied to dragons), and pulp-style adventure.

But pulp adventure isn’t something I’ve really done before. So — true story — I went to my movie shelf, and to novels in the subgenre I intended to write, and started making a laundry list of motifs that show up in them. Hidden treasure! Ancient curses! Booby traps! Impassable terrain!

But pulp adventure isn’t something I’ve really done before. So — true story — I went to my movie shelf, and to novels in the subgenre I intended to write, and started making a laundry list of motifs that show up in them. Hidden treasure! Ancient curses! Booby traps! Impassable terrain!

Archaeology!

Mind you, there’s two kinds of archaeology out there, and only one of them is pulpy. I’m trained in the modern kind, that involves lots of very painstaking excavation and documentation to shed light on societies of the past. Indiana Jones is, shall we say, the other kind. But who can resist ruined temples and mysterious inscriptions? Not me, that’s for sure.

Which is where the Draconeans came from. Aesthetically speaking, they’re part Egypt, part Atlantis: an ancient civilization whose nature and downfall are almost completely unknown in the “modern” day (which is to say, the point at which my protagonist, Isabella, is doing her work; it’s more like our nineteenth century). Their architecture is based on that of Egypt, with megalithic pylons, hypostyle halls, and so on. Their art is Egyptian-style, too; it has the same flat, quasi-2D perspective, the same kinds of striding statues, etc. And they, like the Egyptians, had a writing system that the people of Isabella’s day are struggling to decipher.

But they’re like Atlantis in their mystery. Draconean civilization was much more widespread than the Egyptians ever dreamed of; their ruins are found all over the world. There are vague, mythical references to its collapse. Nobody really knows what the Draconeans were like, though, or why their empire fell. Even the name “Draconean” is a later invention, based on the fact that they worshipped dragons like gods. (Just as the Egyptians frequently attached animal heads to human bodies to represent their deities, so are dragon-headed human figures common in Draconean art.)

Only a little bit of this comes up in A Natural History of Dragons. During the expedition to Vystrana, Isabella visits a small Draconean ruin, which ends up being the site of several later plot points, but Draconean civilization itself doesn’t feature very heavily in the story . . . yet. See, the premise of the series required Isabella to be a natural historian, and I also made her an artist — partly because that’s a skill natural historians frequently had (in order to draw their subjects), and partly because it was an excuse to get some Todd Lockwood sketches as interior art. She has to be moderately competent with languages, in order to adventure all over the world, and needs a certain amount of derring-do. But I didn’t want to make her good at everything, and so I resisted the urge to make her an archaeologist.

That, I’ve saved for a character who will appear later in the series. He will be more than moderately competent with languages; he’ll be a linguist, studying Draconean inscriptions in an effort to break through, the way Jean-François Champollion and others did with Egyptian hieroglyphs. He’ll also be an archaeologist, more interested in the ancient dragon-worshipping civilization than the modern dragons Isabella’s chasing after.

And yeah — if you think the Draconeans are going to be an important plot point in the series as a whole, you would in fact be right. I just couldn’t put it all in Isabella’s lap; she has to work with other people to make the plot go.

But if you want to know where my heart really lies, it’s in those ruined temples, with their weathered art and silent inscriptions and archaeological mysteries. Because I just can’t resist that kind of thing.

EXCERPT

We filed through into a large room enclosed by a dome of glass panels that let in the afternoon sunlight. We stood on a walkway that circled the room’s perimeter and overlooked a deep, sand-floored pit divided by heavy grates into three large pie-slice enclosures.

Within those enclosures were three dragons.

Forgetting myself entirely, I rushed to the rail. In the pit below me, a creature with scales of a faded topaz gold turned its long snout upward to look back at me. From behind my left shoulder, I heard a muffled exclamation, and then someone having a fainting spell. Some of the more adventurous gentlemen came to the railing and murmured amongst themselves, but I had no eyes for them — only for the dragon in the pit.

A heavy clanking sounded as it turned its head away from me, and I saw that a heavy collar bound its neck, connecting to a thick chain that ended at the wall. The gratings between the sections of the pit, I noticed, were doubled; in between each pair there was a gap, so the dragons could not snap at one another through the bars.

With slow, fascinated steps, I made my way around the room. The enclosure to the right held a muddy green lump, likewise chained, that did not look up as I passed. The third dragon was a spindly thing, white-scaled and pink-eyed: an albino.

Mr. Swargin waited at the rail by the entrance. Sparing him a glance, I saw that he watched everyone with careful eyes as they circulated about the room. He had warned us, at the outset of the tour, not to throw anything or make noises at the beasts; I suspected that was a particular concern here.

The golden dragon had retired to the farthest corner of its enclosure to gnaw on a large bone mostly stripped of meat. I studied it carefully, noting certain features of its anatomy, comparing its size against what appeared to be a cow femur. “Mr. Swargin,” I said, my eyes still on the dragon, “these aren’t juveniles, are they? They’re runts.”

“I beg your pardon?” the naturalist responded, turning to me.

“I might be wrong — I’ve only Edgeworth to go by, really, and he’s sadly lacking in illustrations — but my understanding was that species of true dragon do not develop the full ruff behind their heads until adulthood. I could not get a good view of the green one the next cage over — is that a Moulish swamp-wyrm? — but these cannot be full-grown adults, and considering the difficulties of keeping dragons in a menagerie, it seems to me that it might be simpler to collect runt specimens, rather than to deal with the eventual maturation of juveniles. Of course, maturation takes a long time, so one could –”

At that point, I realized what I was doing, and shut my mouth with a snap. Far too late, I fear; someone had already overheard.

RELEVANT LINKS

A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent amazon | B&N | indiebound

BIO

Marie Brennan is a former academic with a background in archaeology, anthropology, and folklore, which she now puts to rather cockeyed use in writing fantasy. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. In addition to many short stories and novellas, she is also the author of A Star Shall Fall and With Fate Conspire (both from Tor Books), as well as Warrior, Witch, Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, and Lies and Prophecy. You can find her online at SwanTower.com.

(Especially since) I was unable to get the copy either of the venues I review for was sent, I Ordered my copy this morning.

Hopefully, Marie, I could impose Lady Trent to sign it, if you come to 4th Street Fantasy this year? 🙂

Absolutely! I hope to make it to Fourth Street again; need to sort out my travel plans for the year when I get home.