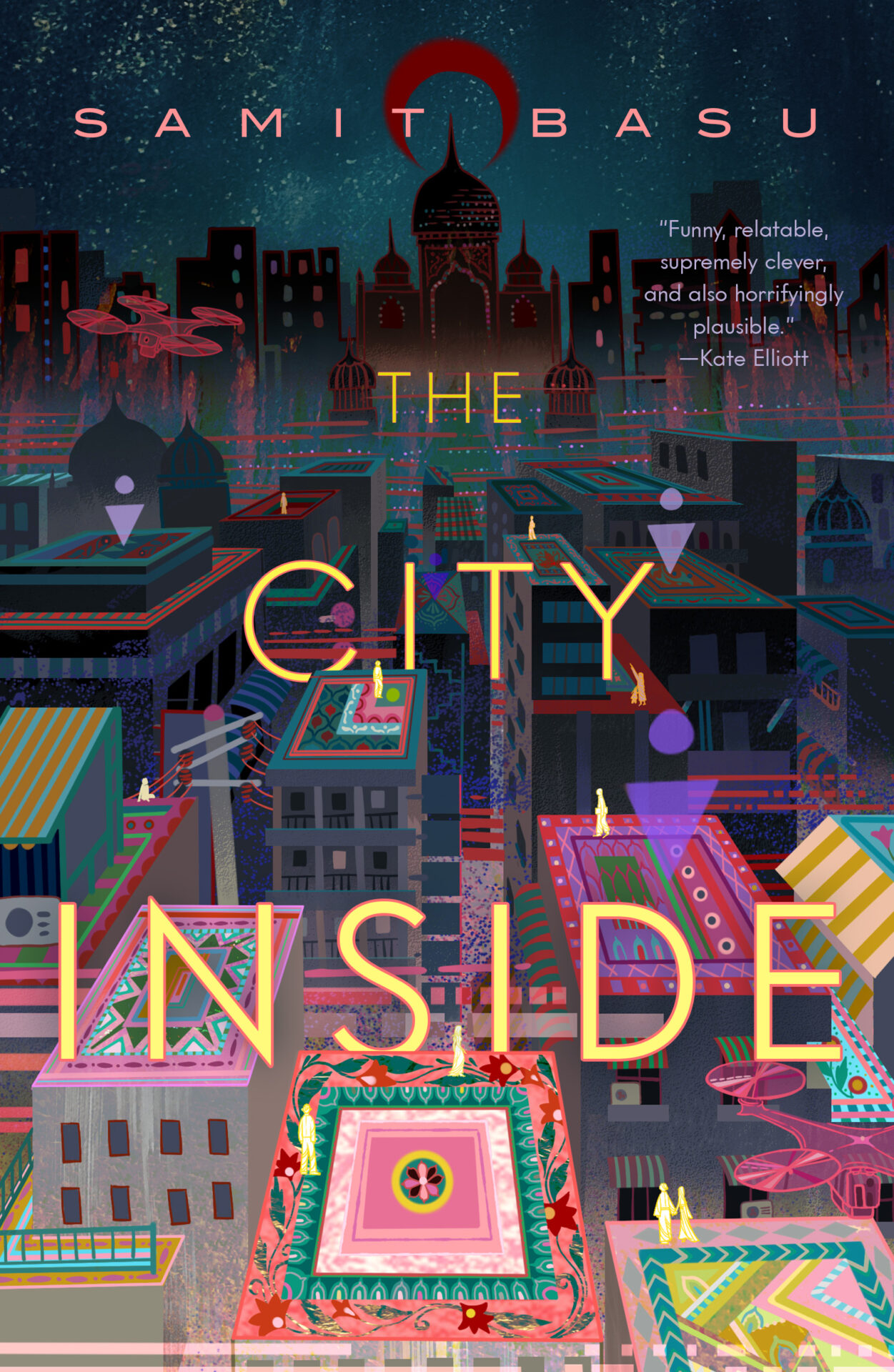

Samit Basu is joining us today to talk about his novel, The City Inside. Here’s the publisher’s description:

The City Inside, a near-future epic by the internationally celebrated Samit Basu, pulls no punches as it comes for your anxieties about society, government, the environment, and our world at large—yet never loses sight of the hopeful potential of the future.

“They’d known the end times were coming but hadn’t known they’d be multiple choice.”

Joey is a Reality Controller in near-future Delhi. Her job is to supervise the multimedia multi-reality livestreams of Indi, one of South Asia’s fastest rising online celebrities—who also happens to be her college ex. Joey’s job gives her considerable culture power, but she’s too caught up in day-to-day crisis handling to see this, or to figure out what she wants from her life.

Rudra is a recluse estranged from his wealthy and powerful family, now living in an impoverished immigrant neighborhood. When his father’s death pulls him back into his family’s orbit, an impulsive job offer from Joey becomes his only escape from the life he never wanted.

But as Joey and Rudra become enmeshed in multiple conspiracies, their lives start to spin out of control—complicated by dysfunctional relationships, corporate loyalty, and the never-ending pressures of surveillance capitalism. When a bigger picture begins to unfold, they must each decide how to do the right thing in a world where simply maintaining the status quo feels like an accomplishment. Ultimately, resistance will not—cannot—take the same shape for these two very different people.

What’s Samit’s favorite bit?

Samit Basu

My favourite bit about The City Inside isn’t in the novel. It’s a trail of folders and files that it left behind as it transformed, over many replannings and rewrites, over several years, into the book it needed to be.

The City Inside is a novel set in Delhi about a decade into the future, and tracks its two protagonists as they struggle to cope with their everyday lives in a world that might look dystopian from the outside but is also one where they are privileged enough to be safe and successful – if they conform, and perform, and look away from the shadows that surround them. Along the way they find ways to grow, hope, resist, and belong. It’s science fiction drawn from nonfiction and the news, and a book about journeys that are internal: from entrapped to active, distracted to focussed, confused to resolute. But the book didn’t start out that way.

I’d intended it to be a grand South Asian cyberpunk/dystopian novel that skipped across decades over the first half of an imagined future century, and contained world-changing tech, heists, secret missions, big action sequences, assassinations and revolutions. And I had the bones of that laid out: if I’d written it in a secondary world, or set somewhere far away, it might have worked.

Instead, it turned out to be a problem that I lived in the city I was trying to describe in science fiction, in a time of extreme change, surrounded by terrible news, real and fake, that kept reminding me that being able to write fiction at all, let alone professionally, was an indicator of huge privilege. And suddenly nothing in my outline or worldbuild felt right, or feasible, and the need for the book to feel ‘real’ kept growing. Which meant the book had to change, and keep changing, even though a lot of work had already gone into it.

So between 2016 and 2019, I built my favourite bit: on the left column of my Scrivener project, a trail of discarded husks of outlines, plans, and then drafts. This includes a year-by-year projected history of South Asia. In it, inventories of increasingly speculative invented technology, violent but hopeful revolutions, multi-directional cyberpunk adventure-times that I hope to use in other books. But none of it was right for this one. I ended up discarding decade after decade, and setting the whole book in what was supposed to be the first part of it: letting go of the here, the now, the real just felt wrong.

I believe that science fiction and fantasy can do anything that any other branch of literature can. I love that these genres and their siblings give their readers and writers not just engagement with the hopes and fears of the present day, but additional clarity and emotion through distance, sheer wonder, and also, sometimes crucially, escape. Sometimes my favourite thing about SF or fantasy is the escape it allows me. But this was not a book where allowing myself escape seemed right: it felt like even more immersion was the way to go. Because in the setting that inspires it, there is no clear escape for those who have to, or even those who choose to live here. You can’t escape through techno-optimism in a place where tech is used as an instrument of exclusion, domination, amplification of privilege. You can’t escape social and political realities: that regime change, for example is often engineered by sinister forces, and destroys the very systems it was supposed to save. You can’t even create a clear knowledge-based worldbuild, or define problems for your protagonists to solve to save the day, when the world around them is specifically designed to confuse, control, manipulate and distract them, and only those with incredible power even know who pulls its strings.

And so The City Inside grew closer and closer to places, fields of work, social environments and actual people I knew. The tech shrank conceptually, and expanded politically and socially, to become extensions of tech that has already been invented, at least in prototype. Real people and places merged to become fictional ones. The news stayed fake.

As the book shed skins and grew more, I decided to follow it in process as well, and completely abandon my comfort zones. I’ve been writing for two decades now, across genres, across media. I feel like I’ve been learning throughout, and also, always, that I know nothing. There are habits you get stuck in, tools you lean on, things you feel like you know how to do, either from within or from feedback over the years. And theres a specific thrill of putting all your favourite toys away, embracing the new and unfamiliar, trying to do things you havent done before, pushing back aspects of craft you’re confident about to foreground others – not as a stunt, but because the book that you’re growing needs what it needs.

I ended up with a story that worked well for people in my part of the world, and I will soon get to find out how people on the other side of the planet feel about it: another leap in the dark. The City Inside was published early in the pandemic’s first wave as Chosen Spirits in India, and most of the edits for the new edition involved writing 2020 and a bit of 2021 into the history, setting and people of the near future in the book. Another section added to my favourite bit before deadlines took the book away from me: a good thing, I’m glad to not still be writing it. I might return to my favourite bit, in time, to pick up abandoned shells and place them elsewhere, but until then it’ll just sit there like an evolution-stage diagram, and hopefully it’ll know it meant a lot to me.

LINKS:

The City Inside Universal Book Link

BIO:

Samit Basu is the author of several novels, most recently of The City Inside (Tordotcom, 2022). He’s been publishing fantasy and SF novels in India since 2003 (The Simoqin Prophecies, Penguin India). His UK/US debuts were in 2012/2013 (Turbulence, Titan Books). Samit has also co-written/directed a film for Netflix, written/produced an animated show, written comics, children’s books and short stories in various genres, and non-fiction as a journalist and columnist. His books have been Indian bestsellers, critically acclaimed in several countries, translated, and in development hell in both Bollywood and Hollywood. He lives in Delhi and on the internet.