B.L. Blanchard is joining us today to talk about her novel, The Peacekeeper. Here’s the publisher’s description:

North America was never colonized. The United States and Canada don’t exist. The Great Lakes are surrounded by an independent Ojibwe nation. And in the village of Baawitigong, a Peacekeeper confronts his devastating past.

Twenty years ago to the day, Chibenashi’s mother was murdered and his father confessed. Ever since, caring for his still-traumatized younger sister has been Chibenashi’s privilege and penance. Now, on the same night of the Manoomin harvest, another woman is slain. His mother’s best friend. The leads to a seemingly impossible connection take Chibenashi far from the only world he’s ever known.

The major city of Shikaakwa is home to the victim’s cruelly estranged family―and to two people Chibenashi never wanted to see again: his imprisoned father and the lover who broke his heart. As the questions mount, the answers will change his and his sister’s lives forever. Because Chibenashi is about to discover that everything about those lives has been a lie.

What’s B.L.’s favorite bit?

B.L. BLANCHARD

I know we’re all here to talk about books, but if you’ll permit me, I’d like to talk to you for a moment about maps.

Maps are soooooo coooooooool.

Okay, got that out of my system.

Here’s the thing about maps: they are not just a directional aid. Like books or short stories or plays or films, they are themselves a form of storytelling. A map tells the story of the past and the present, about the victors of history, and the values of the society drawing the map.

My debut novel, The Peacekeeper, is a murder mystery set in an alternate history that imagines what North America might look like if it had never been colonized. It’s actually a world without overseas colonization, period, but the focus of the book is North America and, specifically, what is known in our world as the Great Lakes region, in an independent Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) nation.

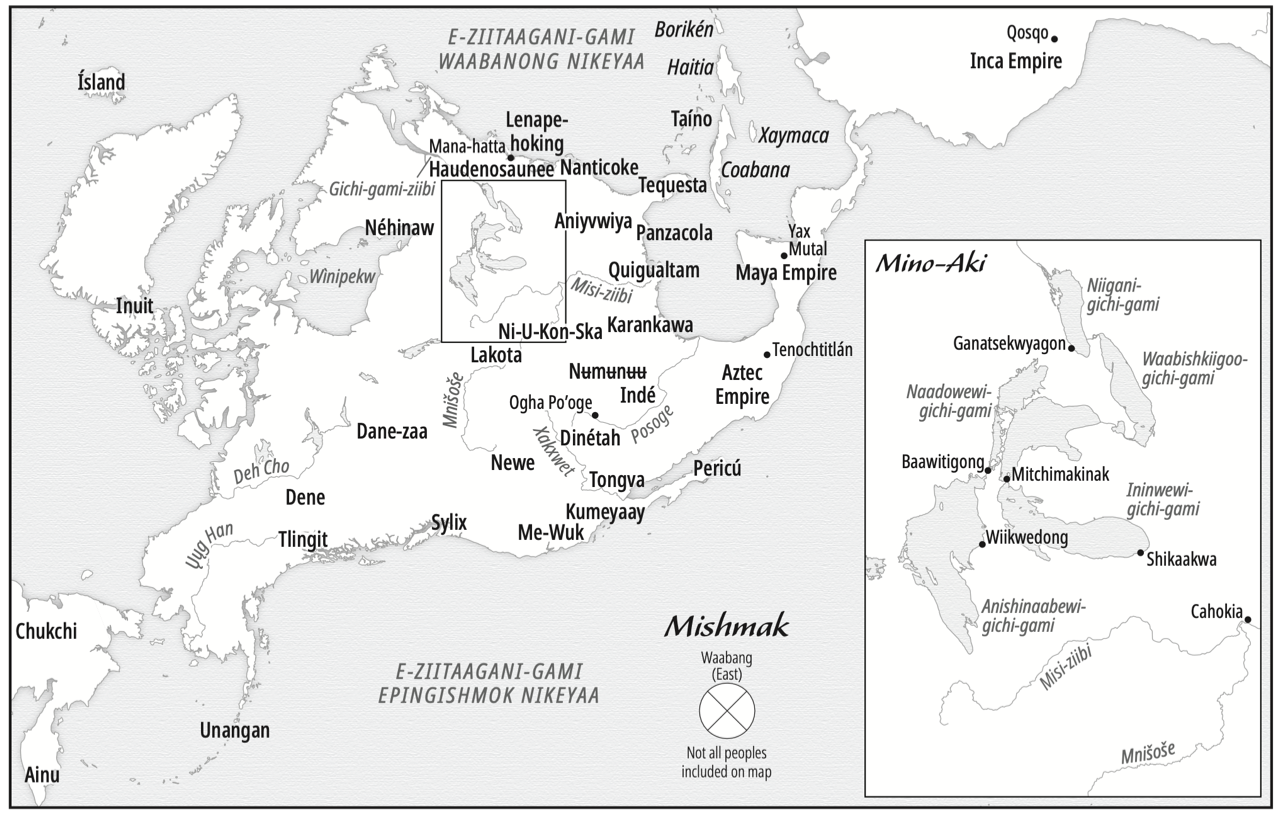

Before we even get into the story itself, the first thing the reader sees when they open the book is a map of what North America looks like in that alternate universe, with an inset for the Great Lakes nation where the novel takes place.

That is by design. The map is part of the story. It is the reader’s first introduction into the world, and without reading a single word of the novel, the reader is being told a story. The map gives the reader 500 years of backstory in a single page.

I have joked with friends that developing the map took almost as long as writing the manuscript. And I’m only really half-kidding when I say that, because that map did take a very long time to develop and research.

The first thing to notice about the map in the book is that it is oriented toward the East, the direction of the rising sun, consistent with Anishinaabe tradition. This means that the map looks “sideways” compared to what we’re used to seeing. Which, fun fact, is actually how maps were typically oriented for hundreds of years. Maps today are typically oriented toward the North due to convention more than anything else. Already, just with its orientation, the map is telling the reader something: this is a story that will be told from a different, but not incorrect, perspective.

The next thing to notice is that the map shows the names of rivers, oceans, and peoples. It shows major cities and names islands in the names used by the Native peoples of the areas. Many of these cities are in the same spot as cities that are familiar to readers of today—Santa Fe, New York, Toronto, Cusco, and Mexico City are all locations of real pre-Columbian cities, but in this map, they are shown with their original names. This informs the reader that there is a largely un-taught history about this part of the world, and that there were and are complex societies in those same places, paved over by colonization. When I first told people about my book idea, I was complimented for the “original” idea of having Native people living in cities. Native people have always lived in cities—there were cities throughout the Americas before colonization, and most Native people in the Americas live in cities today. I’m one of them.

Additionally, the names of the peoples in those areas are ones that may feel unfamiliar to a lot of readers, but that’s because many of the tribal names used today are not the ones that tribes gave themselves. I’m a Chippewa, and we are most commonly known as Ojibwe. But we call ourselves Anishinaabe. Similarly, you’ll find the Cherokee on the map under their own name—Aniyvwiya. Navajo? Diné. Sioux? Lakota. My one regret on the map is that there was not enough room to include all of the hundreds of peoples and nations living there. I aimed for a representative sample, and hope that the map accomplished that.

Finally, I think that what is missing from a map is just as important as what is included. What is not on the map? Borders. Why? Because there aren’t any in this never-colonized North America. People in this world do not draw borders, because that implies that someone could actually own and control the Earth, which is actually inconceivable in this world. Instead, the focus is on the nations—the people. By what is missing, we learn additional information about these nations’ values, and how they differ from the ones dominant in most societies today.

So, if you read a book with a map, please don’t skip it. The map is a story in and of itself. In my book, it’s 500 years of alternate history in a single image. Maps are cool like that.

LINKS:

The Peacekeeper Universal Book Link

BIO:

B.L. Blanchard is a graduate of the UC Davis creative writing honors program and was a writing fellow at Boston University School of Law. She is a lawyer and enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. She is originally from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan but has lived in California for so long that she can no longer handle cold weather. She currently resides in San Diego with her husband and two daughters. The Peacekeeper is her debut novel.